Portraits of the Himba

by Karin Retief

Portraits of the Himba

© Karin Retief, 1997-2000

|

|

Portraits of the Himba

© Karin Retief, 1997-2000

|

Background to "Portraits of the Himba"

The Himba of northern Namibia are striking people, not only because of the dark red ochre they paint on their bodies, but for the way they have chosen to preserve their own unique ways. Self sufficient and totally independent, a plan to build a huge hydro-powered dam on the Kunene river, which runs through their ancestral land, will change their ways forever. I see the flow of the Kunene River as a metaphor for the change the Himba face with construction of the dam.

Now, while the river still flows, the Himba visit their ancestral graves on the banks of the river where guidance is sought from the ancestors. The river is where their cattle and goats go to graze and the women fetch water. But when the construction of the dam stops the flow of the river, the way of life the Himba has known for centuries will stop as well, to make way for

change - the old ways will be lost. I have become close friends with an extended family, who generously took me into their homes and whom I've visited several times since 1997. The book I have in mind will be as much a photographic book as a cultural documentation of a time which inevitably will change in the near future - a celebration of the Himba people and their tranquil world as I experienced it over the last four years. The general public has become more and more interested in the Himba and especially the issue surrounding the controversial Epupa dam has been published widely with great public interest. Apart from highlighting the Epupa dam project and the opposition the Himba has towards such development in their area, the book will also feature the individual people whom I met and spend time with.

Portraits of the Himba

© Karin Retief, 1997-2000

|

|

Portraits of the Himba

© Karin Retief, 1997-2000

|

Story : " Portraits of the Himba "

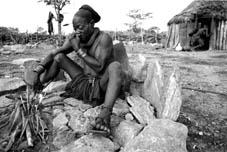

In the early morning, Mbundundu Tjihoto, a headman in the Kunene region, mixes a fresh batch of snuff between his fingers. He is seated on a chair of flat stones extending into a semicircle around an African fire-slow-burning and smoky. His easy movements and the simplicity of the scene in the yard bordered by clay huts and a cattle enclosure hides the significance of the fire-it has been burning for hundreds of years. Keeping alive this holy fire, the umbilical cord between the Himba and their ancestors, comes as naturally to him as the daily ritual of covering himself with a layer of butterfat and red ochre, a trademark which he shares with fellow semi-nomadic Himba living in the arid, rocky region of north-western Namibia. If he is worried about the worst threat ever to face the Himba way of life, his casual actions do not show it. Every morning, his main wife Kombopi takes a coal from the eternal fire that has been kept alive in their hut during the night to the holy fireplace in the open yard. There he tends it throughout the day as one would a child. Through the flame he communicates with the ancestors on behalf of his people.

Today the holy fire of the Himba is in danger of being put out by a plan of the Namibian and Angolan governments to build a huge hydropower dam on the Kunene river. The Kunene river forms the natural border between the two countries. A decision on when the construction of the controversial Epupa hydropower project will begin has been postponed yet again to the end of

2000. Although it was found that a draft feasibility study-done by a consortium of Namibian, Swedish, Norwegian and Angolan consultants-had shortcomings that included the incomplete consideration of measures to lessen the impact on the Himba communities living in the area, the two governments are nevertheless set in their decisions to go ahead with construction.

Building the dam at the Epupa site, which is 7 kilometres below the Epupa falls, would mean the Epupa falls would completely disappear beneath a mass of water covering about 250 square

kilometres of Himba territory and displacing 700 Himba people.

Himba leaders, environmentalists and anthropologists who are opposed to the project see it as economic exploitation. More than a third of the Himba population will be directly effected. Scores of their ancestral burial sites, which they visit in times of crisis, will be flooded. Drowning these ancestral graves will inevitably leave a huge vacuum in their social structure.

Concerns have been raised over the disruption the influx of workers would cause to the Himba way of life. A whole town will be built in the middle of the peaceful and isolated Himba territory. A tarred road would bring outsiders, AIDS, alcohol and a monetary economy, all of which could destroy the intricate and finely balanced social structures that have so far kept

Himba independent and self-sufficient.

Portraits of the Himba

© Karin Retief, 1997-2000

|

|

Portraits of the Himba

© Karin Retief, 1997-2000

|

The omarunga and ongongo trees growing on the banks of the Kunene river will also be drowned. They bear nuts which sustain the Himba in times of drought or livestock disease. The fluctuation of the water in the dam would make it impossible for the trees to grow as they do on the banks of a river. The parasitic disease bilharzia (schistosomiasis) would increase in the stagnant water of the dam, as would the incidence of malaria.

Himba leaders have all vehemently opposed the project-especially chief Hikuminue Kapika of the Kunene Region, who has been in the foreground of the anti-dam campaigns. "There will be no dam here," Kapika told a delegation of the Namibian government who came to the Epupa valley. "We do not want it. This is our land. You have already consulted with us and we have told you that we do not want this dam. It will destroy our land and our cattle."

The Himba community living along the Kunene river has found the Kaoko-Epupa Development Foundation as an alternative to the government's proposed hydropower dam. Solar and wind energy as sources of power would take priority, as well as developing the region's economy while maintaining and promoting the unique traditions of communities in the region. The main aim of the project is for the Himba themselves to be involved in development in their area-not simply leaving it to others, who might want to promote their own interests.

Portraits of the Himba

© Karin Retief, 1997-2000

|

|

Portraits of the Himba

© Karin Retief, 1997-2000

|

Chief Tjihoto, who as a minor leader finds himself outside the fray, also opposes the project, but seems to know little about it. While the Namibian government seems set on going ahead with the construction of the dam against the wishes of the local community he concerns himself with the slow, gentle daily routine of Himba life, which has changed little over many years.

Portraits of the Himba

© Karin Retief, 1997-2000

|

|

Portraits of the Himba

© Karin Retief, 1997-2000

|

Writer Jacques Visagie and I set off from South Africa to the north-western corner of Namibia to find the Himba in 1997. We were doing a story on the proposed dam, which anthropologists and social workers believe will ultimately destroy the Himba as we know them. Before that happens, we wanted to answer a basic question : Who are these ochre-covered people? We were driving through Kaokoland (which means "land of the ochre people") in the rainy season, and we were soon lost because the "road" we were travelling on was nothing more than a single, barely visible track in an area which is called the world's last wilderness. We knew this was Himba land, but because of the dense bush and rain, we had not encountered any Himba since we left a small settlement about five hours' drive east. We pitched our tents but decided not to unpack and make ourselves too comfortable because we weren't sure how the Himba would react to strangers just making themselves at home in their area. We wanted to meet the headman

first and ask permission to camp on their land the next day. Just before sunset, the rain stopped, allowing us to make a fire to warm ourselves and cook. I could hear singing and laughter in the distance and the sounds of sticks breaking and stones moving about. I could also feel eyes watching us. But no one came to meet us, and we went to bed knowing a sleepless night and uneasy dreams awaited us. Before dawn the next morning, I heard the distinctive sounds of someone approaching our camp. I peeped through my tent to see a tall, slim man approaching our burnt-out fire. Grunting and making sounds as if he was talking to himself, he circled our fire, pushed his skirt between his legs (as is the custom), and bent down to sit on his heels. Then he started scratching in the ashes with his walking stick. Finding a small ember, he gently added small sticks and started blowing on the coal until it smouldered and he slowly started our fire again. I exhaled and knew it was going to be all right. His name was Kakuve and from that day onwards (because, as he said, he had "found" us) he took the role of our guardian and advisor. That first morning, all of the elder men of the homesteads in the area visited us. We knew the headman had arrived when a man walked up and pointed to the folding chair Jacques was sitting on, claiming it for himself-as he did during every visit thereafter. After many cups of coffee and difficulties communicating through hand signals and gestures, we asked permission to camp. We indicated we wanted to stay for roughly a month and half by pointing to where the sun rises and then following the sun's path to where it sets-roughly 45 times. The first couple of days the men visited us regularly, with Kakuve arriving each morning for his cup of sweet coffee before heading off for the day's work. The headman, too, would arrive most mornings for a cup of coffee. After his coffee, he would take deep draughts of his peppermint-tobacco snuff, then rest his head in his palm and doze off for hours at a time. Then the children slowly overcame their shyness and started visiting us. Only after almost a week did the women slowly appear-and then always standing a distance away,observing us. Menjamwapi was in the first group of women who visited us. I remember her standing a short distance away watching every movement I made. She would giggle and chat at the same time, hiding her face behind her hand. She was the most beautiful woman I'd ever seen, with a mystical energy that drew you into her world of peace and harmony. I was captivated and wanted to sit down and observe THEM, but we couldn't just sit there staring at each other, so I carried on with chores. The most difficult part was not taking pictures because everything was so wonderfully new and different. But I did not want to impose myself on the families and waited until I was invited to their gardens. Even then I waited a couple of weeks more before taking photos without them being conscious of me or the camera. The Himba grow "mealies"-corn-in their gardens. Together with milk, which is drunk as yoghurt, corn forms the Himbas' main diet. As a photojournalist, the most difficult obstacle was to stay objective. I found the longer I stayed, the less I was "seeing the pictures." And the more I became friends with the Himba, the more I just wanted to spend time with them and not think about photos at all. It was February, the hottest time of the year in Kaokoland as well as the rainy season, which meant a large insect population. Getting out of your tent in the morning, the flies would cover you like a thick black blanket. Luckily they would disappear as the sun started heating up (around 38 degrees Celsius). At night big spiders and scorpions would come to our fire; we gently scooped them up and removed them to a safer distance. But if Himba men were visiting our camp, the spiders stood no chance of survival. We thought that if we did not kill anything, nothing would kill us. This philosophy the Himba found most preposterous, as so many Himba, especially children, get very sick and sometimes die from the bites and stings of snakes, scorpions and spiders. One night we found a metre-and-a-half python hanging on a branch over my tent. We made a cup of tea and sat about 3 metres away, watching this beautiful creature for hours, first going up and then down the tree before heading off into the bush. We had to collect our water from a wind pump about 300 metres away. On one of my visits there I met Twakoseka. She was the funniest, most outspoken and most rebellious of all the women I met. We would sit for hours and "gossip" with sign language and the minute bit of Herero (the Himba language) I was starting to pick up. The first time we met, it started to rain and I hid with her and two other women under a tree. She couldn't understand that someone at the grand old age of 30 did not have a child and wanted to see my breasts as proof. With much interest and comments that I wish I could have understood, they discussed my breasts. And when some more women arrived a little later Twakoseka insisted that I show them this phenomenon as well. When I went back to visit them a year later, she could not believe that I STILL did not have a child and again I had to bare my breasts as proof! The headman, Chioto, had three wives, but Twakoseka was his favorite girlfriend, as he showed me many times. Slowly my life with the Himba got a peaceful rhythm and I would spend most of my day away from our campsite. I would be up at dawn and visit one of my three favorite homesteads until mid-morning. There I would sit with the women and share in the warm fresh milk of the morning. The children had to separate the young calves from their mothers and anyone daring to come too close while their mothers were being milked would get a whack on the nose. This would take place in the cattle enclosure which is a fenced-off area in the middle of the homestead. Mornings had a cheerful, noisy blend of laughing children and bleating calves. The homestead consisted of three or four huts. The huts, made of wooden poles, are plastered on the outside with a mixture of cow dung and clay, forming a solid waterproof crust. On entering the homestead, I would always avoid walking across the area between the opening of the cattle enclosure and the holy fire, which would have been considered extremely rude. The holy fire burns in the area in front of the headman's hut, where he tends to it throughout the day, making sure it never dies. At night his main wife takes an ember from the holy fire into their hut, where it smoulders throughout the night. At dawn, she returns the ember to the holy fireplace. Thus, the holy fire of the headman has been burning for centuries. I spent the afternoons either in the gardens or walking the cattle to the grazing fields with the teenage boys. I would find Menjamwapi in her family's garden, with her baby boy wrapped firmly on her back, grinding an ochre stone into powder. This ochre powder she mixed with butterfat to make the characteristic red ointment that covers every Himba's body and clothes. As she ground, her body would sway to and fro to the rhythm of a murmured melody. Small black lines would form down her arms and chest where sweat has cleared away the ochre from her skin. Sometimes her cousin Mukakamunwe would join us under the tree. The eleven-year-old was always at hand to help with Menjamwapi's baby. Her hair was neatly plaited into the customary four braids of girls her age. Two of the thick braids hung forward over her face. When she enters puberty, her mother will loosen her hair and plait it into dozens of braids that will cover her whole face. She will peep shyly from behind the braids until she enters womanhood. Then she will tie her hair to the back of her head, leaving her face open for the first time. During the day, the gardens are the domain of the women, who spend most of the day working there. Breaks are spent in the shade of trees, where they carefully beautify themselves with the butter and ochre mixture. The grown men spend the day visiting neighbours and exchanging news. Their teenage sons walk the cattle to the grazing fields and sit under blankets to shelter themselves from the sun. Most of the day is spent drinking milk, singing and listening to long, sorrowful tunes played on the kaekundu, a bugle-like instrument made of antelope horn and clay. Some wear colourful cotton shirts, probably from the United Nations office in the nearest town. They sit or lie intermingled, with an almost visible bond between them. They unconsciously touch each other, straightening a bangle on another's arm or holding hands. At what seems to be bonding ceremonies, groups of teenage boys occasionally sit down in a circle, all ornaments and clothing removed from their bodies except for their loincloths. They spend the afternoon drinking a home-brewed wine and enthusiastically discussing internal politics, the rain and cattle. Sometimes they slaughter a goat and sing and dance into the night. At nightfall the young men return, bringing with them the cattle, long shadows and the red glow of the setting sun. Their younger brothers and sisters chase the goats they had been tending during the day into the animal enclosure. The air at the homestead turns into a vibrant chaos of cheerful flirting and teasing, which continues until after dark. The Himba settle around their fires, drinking sour milk and exchanging stories of the day and perhaps stories of the past: how their ancestors came to Kaokoland from the north, were driven back by the Nama and saved by their great leader Vita; how they came through the more recent guerrilla war of independence between SWAPO and the South African colonial forces; and how they survived the worst drought in living memory in the 1980s. And when the conversation and laughter die down, Kombopi takes a coal from the ancient fire into the hut of chief Tjihoto, where it would keep on burning through the night.

--------------------------------------

A year later I visited "my" family again. After months of planning, saving and worries that I would not find their remote area again, I arrived to find most of the huts abandoned. The Himba are semi-nomadic and move between two or more homestead areas, depending on the rain. Finding only an elderly couple who could not make the trip, I realized that to go and search for them would be futile. I only had enough jerry cans filled with diesel to get me back to the nearest pump, about 400 kilometers away. With my heart in my shoes and contemplating what to do, I heard a horse galloping towards my direction and turned around to look into the smiling face of Tjarambwa, a teenager I knew. Settling down by my fire, he explained that the family went away for the season because it did not rain in their area that year. I enquired about Menjamwapi and the other women I knew. He said that because

Menjamwapi had just given birth to a baby girl, she could not make the journey and had stayed behind with other women to look after the youngest children, who also could not make the journey. She was at a homestead about 5 hours' walk from where I was. I set out early the next day and met Twakoseka halfway. She had a cracked piece of paper (torn from a 1920's book) with her stained red with ochre and bearing a hand-written message in Herero from Menjamwapi. The note said she was happy to hear from Tjarambwa that I had come back to visit and wished that she could see me, but that she had just given birth and was therefore unable to walk the distance. Later I found her at the homestead, where we had a happy reunion. After humorously discussing the photos of her and her family I had taken the previous year, we settled down in the cool of her hut. She told me about the new baby and how she was in labour for three days. We were two women from such different realities, yet so easy in understanding each other and so similar. When we said our farewells, she said that her baby should have a

second name and opted for Karende (the name the Himba called me), in

celebration of our friendship.

--------------------------------------

Note : This year (2000) I visited the Himba again - my god-daughter is now 2 years old

|