Electric Light As A Medium In The Visual Fine Arts: A Memoir

Leonardo, Vol. 8, pp. 109-119. Pergamon Press 1975. Printed in Great Britain

by FRANK J. MALINA *

Abstract The author describes how he was led to work with kinetic electric light art objects of the Lumia type in 1954. He then discusses the problems of applying light for artistic purposes from the point of view, primarily, of his own experiences with kinetic painting systems. These include the direct transmission of light to the eye or onto a translucent screen (Lumidyne system), the production of reflected light images on a translucent screen (Reflectodyne system) and the transmission of light through polarizing materials (Polaridyne system). Technical details of the systems are given and the reactions of viewers of these kinds of art objects are briefly presented. The author states that, although he is a reluctant prophet, he would not be surprised if a wide acceptance of kinetic art with electric light must await the passage of several more decades.

I.

Electricity for providing light began to be used broadly in industrial countries at the beginning this century. Although electric light sources were quickly adopted for photographic lighting and for cinema projection, it was accepted in a limited way as a fine art medium only in the 1950’s [1-4]. The first generation of pioneers in the application of electric light in art at the beginning of the 20th century developed methods for producing light images in motion and with changing colors mainly as spectacles for presentation to theater and cinema audiences. The second generation of pioneers in the 1920’s and 1930’s began to construct art objects incorporating electric light for individual contemplation. However, it was not until the third generation arrived on the scene after World War II that objects of this kind began to be shown in numerous museums and to be sold in galleries.

I began working with electric light towards the end of 1954 without being aware of what artists had already done with the medium. Serendipity gave rise to my interest in it. Between 10-23 June 1954, I exhibited at the Arnaud Gallery in Paris a group of pictures incorporating the moirC effect produced by means of superposed layers of wire mesh (Fig. 1). They would now be called examples of Op art. To increase the contrast between a moiré pattern and its background or support, I tried various ways of painting the mesh and the support, only to find that none of them was effective enough. In frustration, I held an electric lamp of about 50W in back of the layers of mesh. What I saw gave me of that feeling of ecstasy that one experiences on making a personal discovery-one could use electric light as an art medium!

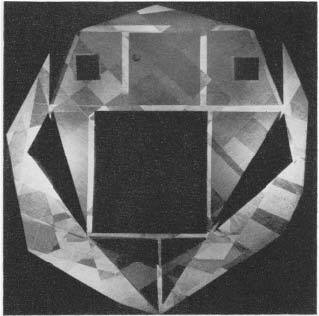

Fig. 1. ‘Deep Shadows’

No. 708/1954,

Op art picture painted wire mesh and wood, 71 x 54 cm.,

1954.

Collection of Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris, France.

© Marc Vaux

| |

The fact that I recognized the possible significance of my experience resulted from an obsession that began to absorb me in the 1930’s, especially while I was carrying out research on rocket propulsion and flight at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). I was one who did not stop drawing after childhood and I earned money for my education at Texas A. and M. University and Caltech partly by making technical illustrations for books (Technical Drawing by F. E. Giesecke, A. Mitchell and H. C. Spencer, 1936, Design of Machine Elements by V. M. Faires, 1934, and Mathematical Methods in Engineering by Th. Von Karman and M. A. Biot, 1940). I also read widely on the painting and sculpture of my time and that of the past. Since I believed that science and technology were of vital importance for the mental and material welfare of people, I found it disturbing that so few artists gave attention to the philosophical and visual aspects of these activities [5, 6]. By the time I embarked on a career in art in Paris in 1953, I was saturated by the vast quantity of paintings of nudes, flowers, landscapes and deadfish that filled the museums and galleries. Earlier I had tried to introduce so-called nonfigurative subject matter into pastel drawings and paintings but the results did not satisfy me. An image of electric lamp first appeared in a wire relief picture that I made in 1953 (Fig. 2). My mind was thus prepared to respond to the vision provided by the light from the electric lamp that I had placed behind the layers of wire mesh.

My engineering research training should have led me to make a search of the literature on the use of electric light in the fine and applied arts (even though indexing of work by contemporary artists was then notoriously poor) but I did nothing of the sort. As is the common practice of artists, I blundered ahead to repeat the errors and to miss the contributions that my predecessors had already made to the subject. Sometimes this procedure can bring about a viable development in an unexplored direction but the chances of success are small.

Since I had been making Op art-type pictures with wooden frames and supports, for my first try at using electric light I inserted a lamp of about 50W into such a construction. In a few minutes the hot lamp caused a column of smoke to rise from the charring wood! I said to myself that I now understand why electric light is not suitable in art objects and gave up my attempt. A few months later I sat in my studio looking at our Christmas tree with its string of small bulbs-they did no harm to the tree. How stupid I had been not to have thought of installing lamps of low wattage in the picture!

After the tree was taken down, with one of the strings of bulbs I made my first electric light picture ‘Illuminated Wire Mesh Moiré’ (1955), which I called an electropainting. My uncertainty as to its merits was dispelled by my good friend, Sandy Koffler, editor of the Unesco Courier, who reacted to it with enthusiasm when I showed it to him. From this point on, electric light has been my principal medium and I have used it in about 250 two- and three-dimensional works.

II.

The basic technical problem confronting an artist who wishes to use electric light is how to control it, to make it respond to his wishes. In the traditional arts of painting and sculpture, light from any source is reflected to the eye from materials that the artist can manipulate, that is, the materials are said to be ‘plastic’ in the sense that they can be shaped or formed into art objects. Light from any source cannot be handled like paint, clay and metal because of its different physical characteristics.

Advantage can be taken of the properties of light that permit it not only to be reflected and refracted but to be changed in wavelength composition (for colors to be perceived), for example by means of light filters or light polarizers together with birefringent materials.

Electric light sources themselves, to a limited extent, can be manipulated to form an art object. Arrays of incandescent and fluorescent lamps can be used to give shapes in different colors and the glass tubing of neon lighting in the hands of as killed craftsman can be formed into linear structures. Although these techniques have long been applied in advertising signs, it was only in the last decade or so that they have found their way into fine art objects. In my view, the use of light sources themselves in such objects severely limits artistic expression because of the inflexibility imposed by their very construction. This is borne out by the fact that but few artists have chosen this road of using electric light.

Fig. 2. ‘Light Globe’

No. 566/1953,

relief painting, painted wire,

wire mesh and wood, 59x49 cm,

1953.

© DR

| |

If light sources themselves are not to be a visible part of an art object, how have artists used electric light? There have been three principle ways: (1) Transmission of light from within an object directly to the eye or onto a translucent screen or external projection of it onto an object; (2) production of shadows of shaped materials and of light images produced by refraction and by reflection from mirrors and polished surfaces onto a translucent screen or onto an opaque surface and (3) transmission of light through light-polarizing and birefringent materials.

Perhaps because of the limitation of taking advantage of electric light in still or static art objects, already the first generation of pioneers turned to the production of visual experiences that involve motion and changes of color with time. The generally accepted term for works of this kind is kinetic electric light art.

III.

Before discussing the three principle ways in which electric light has been used, the following comments will be helpful. Artists are well advised to avoid, as much as possible, uncommon kinds of electric light sources and subsidiary equipment. One frequently finds kinetic art works in exhibitions that are not operating because a replacement of one of their electrical components could not be found, even in stores in large cities. Standard ordinary lamps are preferable, with color obtained by means of permanently installed color filters. The lack of an international standardization of fittings and the ‘consumer’ society plague of manufacturers' making unnecessary changes in the design of electrical parts are present-day nuisances for artists who apply electric light in art objects.

Few museums and commercial galleries at present have qualified personnel to deal with the installation, maintenance and conservation of kinetic art works that utilize electricity. A manual on these matters is badly needed. When arranging exhibitions, I ask the museum or gallery to provide an electrician familiar with local conditions to assist with the mounting of the works. My experience has been that a collection of 15 to 25 of my works can be installed in one day. On the back of each of my objects is the statement: ‘The mechanism is simple and can be put in order by any electrician or radio repair man.’

The general ignorance of even the simplest aspects of electricity causes most people to fear unreasonably any kind of electrical device. On the other hand, artists trained in traditional media who decide to use electricity do not fear it enough, either from the point of view of causing harm to themselves or of making art works that do not meet minimum safety standards. An artist should have the electrical system that he has chosen checked by a qualified electrician.

The rudiments of the simple circuits and the characteristics of the different kinds of lights, electric motors and other components mentioned in this article can readily be learned from books written for the layman.

Artists use the following major types of electric light sources: (1) household incandescent lamps or bulbs and (2) fluorescent lamps or tubes; (3) neon light tubes, widely used in advertising displays, and (4) special purpose incandescent lamps of high wattage that may have reflectors built within them or are designed to flash. Sheet lighting, whose color can be varied by changing the frequency of the input electric current, still in the development stage, would offer interesting artistic possibilities. Incandescent lamps above about 15W pose temperature problems when they are enclosed within an art object. Their lifetime, unless they are operated below their recommended voltage, is several hundred hours. The light they provide has a warm yellowish tint. Fluorescent and neon tubes pose no temperature problems but the components in their circuits may do so. Also these components are relatively heavy, which may be an important consideration for some art objects. Whenever any of these types of light sources are enclosed within an object, convective air cooling must be provided. This can usually be done by simply providing air inlet and outlet openings, which should be shielded internally to prevent light leakage.

Motion of parts in kinetic art objects is obtained generally by means of synchronous or variable speed electric motors that are manufactured in small dimensions with a wide range of turns or fractions of a turn per minute.

The voltage of household electricity varies from country to country and even from city to city. It is generally either about 110V or 220V. Most electrical parts can be obtained that can be adjusted for either voltage. If a work is not provided with the required parts, then a voltage transformer can be placed in the input circuit, as necessary. Electricity of alternating current is generated at 60 Hz (i.e. 60 cycles/sec) in North America and at 50 Hz in Europe. This poses no problems as regards light sources but synchronous motors designed, for example, for 50 Hz will turn 20% faster if operated at 60 Hz and those designed at 60 Hz must not be used at 50 Hz.

IV.

Now I shall return to my discussion of the three principle ways in which electric light can be used as an artistic medium on the basis of my own experience.

1. Transmission of light from within an object directly to the eye or onto a translucent screen or external projection of it onto an object.

A stained glass window is an example of an object using the direct transmission of light through a surface made up of transparent, translucent and opaque materials. My electropaintings are of this type of visual art. They are made in the following way: Incandescent clear or opal (frosted) lamps of up to 15W or fluorescent tubes are mounted on the rear surface of a case or frame and light is transmitted or projected through a pictorial surface directly to a viewer’s eyes. The pictorial surface, placed near to the light sources, consists of a translucent sheet or plate on which a composition is either painted or made up of a collage of various materials of different colors and transparency (Fig. 3). Stained glass can, of course, be used but it has the disadvantages of being both heavy and cumbersome. Most of my works with electric light have been designed to permit their installation on a wall like traditional paintings. Therefore, they must be as light in weight and small in depth as possible. These specifications pose fairly difficult engineering problems and some artistic possibilities of electric light have to be sacrificed, especially if the objects are of a kinetic type.

Fig. 3. ‘On a Strange Planet’

No. 803/1955,

electropainting, wire mesh, tracing paper,

colored Cellophane, wood and incandescent lamps,

45x61 cm,

1955.

© Marc Vaux

| |

Fig. 4. ‘Jazz’

kinetic electropainting.

painted wire mesh, tracing paper,

colored Cellophane, wood and incandescent lamps

with thermal interrupters in circuits,

50x77 cm,

1955

© DR

|

One can convert a static electropainting into a kinetic work simply by resorting to flashing lights. In 1955, I made my first kinetic electropainting with incandescent lamps whose flashes were controlled by thermal interrupters in the electrical input circuit of each lamp. An example of such a work, entitled 'Jazz', is shown in Fig. 4. The composition consists of eleven shapes illuminated by eight on-off flashes of about one sec. duration and by three of about five sec. duration. Since the interrupters are not precise in their timing, the moment of the appearance of any of the eleven shapes is not predictable. There are 211 = 2048 possible combinations that follow each other in random order. The flashes at times appear to have a definite rhythm that becomes especially noticeable when the picture is viewed while listening to music with a rapid tempo.

A collection of my static and of kinetic electropaintings was shown at the Colette Allendy Gallery in Paris between 5-19 July 1955 [7]. This may have been the first exhibition of kinetic electric light art in France.

Fig. 6. ‘Kinetic Column’

No. 925A/1961,

kinetic sculpture, Lumidyne system,

fluorescent tubes, 150 x diam. 30 cm.,

1961.

© DR

| |

Although several artists [2-4, 8] also have made works with the flashing lights technique, including computer programmed flashes of arrays of lamps, I find that this technique severely limits artistic expression and disturbs one's contemplation of the work. This conviction led me in 1956 to search for a way to produce a kinetic picture with continuous motion and continuous changes of colored light.

A continuous variation in the light intensity of incandescent lamps can be produced by means of, for example, variable resistances or of thyratron tubes in their circuits but I do not believe that this approach is a promising one. It might be combined effectively, however, with some of the kinetic systems that I shall describe below.

Jean Villmer, then an electronics student, assisted me with the design of electric and electronic circuits about which my knowledge was too elementary. After we had struggled unsuccessfully to devise a convenient circuit for varying the light intensity of lamps, he suggested that an electro-mechanical system might be a simpler way of obtaining continuous motion and color changes. We then proceeded to construct one within a case consisting of light sources in front of which were a transparent disk or rotor turned by a synchronous motor and, in front of the rotor, a static component or stator of transparent sheet or plate.

When designs on the rotor and stator are made with opaque paint, allowing light to pass through some portions of them, one sees on the stator illuminated points that move or shapes that continuously change. When I saw the resulting picture I was not satisfied with it and only several years later did I realize that the system had interesting artistic possibilities. On the basis of my experience with electropaintings, I placed a translucent sheet of tracing paper or a diffusor about 2 cm in front of the stator. The resulting transformation of the picture produced by the rotor and stator was startling and pleased me immediately. I called the combination of light sources, rotor, stator and diffusor the Lumidyne system for kinetic painting. Technical details of the system and on its artistic use can be found in Refs. 4, 9 and 10. In Fig. 5 (cf. color plate) is shown the mural ‘The Cosmos’, an example of a Lumidyne kinetic painting in which there are 29 rotors and both incandescent and fluorescent lamps. A three-dimensional application of the system to a ‘Kinetic Column’ is shown in Fig. 6. In this work the rotor, stator and diffusor are circular cylinders and two fluorescent tubes are installed along the central axis.

It was not until 1964 that I began to make works without a diffusor or what I call a 3-component Lumidyne system (lights, rotor and stator). ‘Cosmic Life’ in Fig. 7 is an example of such a painting. When a diffusor is used (Fig. 5), the picture seen might be said to have a soft, mysterious, lyrical quality and highly complex motions of light images can be introduced, including motion opposite to the direction of rotation of the rotor, especially when there are line sources of light from fluorescent tubes. A 3-component Lumidyne painting has a hard-edge character. A translucent rotor may be used and a painting can be made on the stator for viewing in ambient light when the electricity is stopped. The 3-component system is suitable for making kinetic-Op art pictures, that is, the visual effects used in static-Op art, for example, the moiré effect, can be made kinetic. The translucent diffusor absorbs light, so it needs to be viewed in more subdued ambient light than a 3-component Lumidyne painting.

An advantage of direct transmission of light, as in the Lumidyne systems, is that the works can be viewed in rooms with normal electrical illumination. I believe that systems requiring the darkening of a room in order for the picture to be viewed adequately are severely handicapped in the contemporary world.

The Lumidyne systems offer to artists considerable flexibility both as regards subject matter to be depicted and the development of a personal artistic style. The composition of a Lumidyne painting is fixed and is determined by the image painted or otherwise formed on the stator. The rotor design controls the motion and color changes within the composition. Several artists have worked in my studio with the systems, amongst whom Nino Calos [l, 2, 4] and Masako Sato [4] have made and exhibited numerous Lumidyne system works of their own. A description of the work of Giorgio Giusti with a variant of the Lumidyne system can be found in Ref. 11.

In 1961 I visited the late A. Michotte [12] at Louvain University in Belgium, because I had learned that he had long been doing research as an experimental psychologist on the perception of motion. I was amazed to find that he was using the basic principle of what I call the 3-component Lumidyne system in some of his studies. He did not use electric light but had a rotor of paper on which designs were drawn and in front of it a paper stator with designs cut out of the paper. He then studied the reactions of viewers to the motion of points moving in different ways in the cutout stator slots. He produced a quantity of sets of rotors and stators for demonstrations to students of the psychology of perception but, although I tried for many years to obtain one, I have failed to do so [13]. They are a most valuable source of ideas for kinetic art. When I asked him if he had given any thought to the aesthetic aspects of images in motion, he replied that it had never occured to him to do so.

Another surprise awaited me in 1967 while visiting D. Accursi, director of Jouets et Automates Français (J AF) in Paris. On the shop floor of the company was a large piece with several 3-component Lumidyne system pictures around its periphery. I was told that it was built in accordance with designs developed in France in the 18th century but I have not been able to trace data on its origins. Perhaps oil lamps were a source of light and the rotor was hand or spring driven. It is evident that light images in motion have long intrigued those with artistic inclinations.

The projection of, electric light with changing colors to illuminate and also to produce stroboscopic effects on static and kinetic three-dimensional objects has been applied by artists; however, the aesthetic potentialities of such an approach seem to me to be very limited [2-4]. I will discuss below a variant of this approach.

2. Production of pictures made up of shadows and reflected light images on a translucent screen or on an opaque surface.

Electric light compositions in motion and with changing colors made visible on a translucent screen were called Lumia by Thomas Wilfred [14], who began working with electric light in 1912 and continued to do so until his death in 1968 [14]. I first saw one of his Lumia works at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in about 1959. He did not publish the details of the construction of his various Lumia systems but the one he used in art objects basically depends on the projection of light through color filters and its reflection from polished or mirrored formed surfaces onto the rear side of a translucent screen or diffusor. I visited him at his studio in West Nyack, New York, in 1964 and met with him in Eindhoven in Holland during the exhibition ‘Kunst Licht Kunst’ (Art, Light, Art) at the Stedelijk van Abbemuseum in 1966. On neither of these occasions was he interested in discussing his Lumia systems and, furthermore, he had a lock on his objects, a measure of doubtful value for preserving secrets if one offers one's works for sale, as he did.

Fig. 7. ‘Cosmic Life’

No. 1039/1968,

kinetic painting,

3component Lumidyne System,

fluorescent tubes, 80x60 cm,

1968.

(Malina Science and Art Competition Trophy,

Oundle School, Oundle, England.)

© Barton

| |

In 1959 André Louis Hirsch, of the Louis Hirsch Bank in Paris, an enthusiast of astronautics, agreed to my proposal that a commercial company be formed with the objective of developing kinetic electric light devices for advertising and artistic applications. The company was given the name Electra Lumidyne International (ELI). One of the projects of ELI that I carried out in 1962-1964 was for the General Electric Co., Radio and Television Division, Syracuse, N.Y., U.S.A., under the supervision of Robert G. Page. The objective of this project was to develop an audio-kinetic electric light art device suitable for mass production. General Electric had made a market survey in the U.S.A. that indicated that there might be a large market for such a device for home use and provided me with two different prototypes that the company had constructed on the basis of information obtained from various sources.

The system of the first prototype (called ‘Chromie No. 1’) consists of a light-tight case with a translucent screen or diffusor at the front. A clear incandescent lamp of about 60W at the side of the case is in a container provided with an opening through which a beam of light is projected through a rotating color wheel into the image-making compartment. The beam then impinges on a small flat rotating polished aluminum disk placed at an angle to reflect it to a larger shaped vertical polished aluminum rotor and from this rotor is reflected an image onto the diffusor.

| |

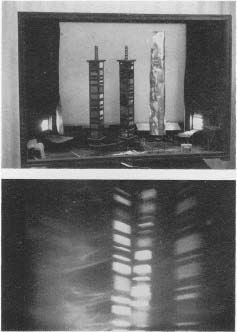

Fig. 8. ‘Entrechats, II’

No. 985/1966,

audio-kinetic painting, Reflectodyne system, 60x80 cm.,

1968.

Above: Interior view. Below: An image on the diffuser.

(On loan to Palace of Arts and Science, San Francisco, USA)

© DR

|

The second prototype (called ‘Chromie No. 2’) is an audio-kinetic object in which the motion of light images reflected onto a diffusor is controlled by the intensity of sound. This is accomplished by projecting light from a special clear 150W incandescent lamp (Type GE DFA) with a built-in reflector onto a small aluminium foil mirror mounted on the needle of a potentiometer whose deflection is dependent on the intensity of sound within a selected frequency range of the sound input. The light from the mirror is then directed onto a single rotating shaped polished aluminum rotor from which it is reflected onto the diffusor. There are three such units directed at the rotor-one for the low, one for the medium and one for the high frequency range into which the sound input is separated. In front of each lamp a filter of different color can be placed. Since the General Electric Co. was interested in an audio-kinetic object, I was asked to attempt to design one that gives a more varied and interesting visual experience than their prototype.

Taking into account the design of the above prototypes, I devised what I call a Reflectodyne system for producing either a kinetic or an audio-kinetic picture. In Fig. 8 (above) is shown the interior of the audio-kinetic painting ‘Entrechats, II’ with the Reflectodyne system and (below) one of the images produced on the diffusor.

A Reflectodyne system kinetic painting consists of a case with a clear incandescent lamp (I use a lamp of 100W) in a compartment on one or both sides of the interior of the case, provided with an opening through which a beam of light is projected into the central portion of the case or image-making compartment. Clear lamps are used, because the bright lamp filaments add to the complexity and visual interest of the images produced. The colors to be perceived in the light beam may be varied by placing motor-rotated filters (a color wheel) in the path of the beam as it leaves the light compartment.

The light beam strikes mirrors or polished shaped metal surfaces in motion in the image-making compartment that reflect the beam to produce colored images on the diffusor, which makes up the front of the case. In the simplest version, the Reflectodyne image-making compartment has one or more vertical rotating rods. To these rods are attached shaped reflecting surfaces and I call these rods with their reflectors trees. Shaped reflecting surfaces can also be fixed behind the trees to give supplementary light images and shadows of the reflecting surfaces on the diffusor. The trees are rotated at different speeds (in a clockwise or counterclockwise direction) by means of a chain or gear drive by a synchronous motor in order to obtain a cycle of a desired period of time in minutes, hours or days. If the color wheel and/or the trees are rotated by a friction drive with unpredictable slippage, then a cycle of infinite duration can theoretically be obtained.

This raises the question as to the importance of the length of the cycle of the constantly changing composition in Lumia-type kinetic art. My observation of viewers of kinetic art indicates that visual memory is of such short duration that kinetic works with complex images whose cycle is as short as one minute are adequate. This is especially true in view of the fact that few art lovers concentrate their attention on a work for more than several minutes. My Lumidyne system kinetic painting ‘Polaris, I’ (1956) (collection of Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institute, Washington, D.C., U.S.A.) incorporates in the composition a depiction of the Ursa Major (the Big Bear or Plough) star constellation along with the Polar star. The constellation is visible for a few seconds about every 90 seconds. Viewers find that the 90 seconds seem psychologically much longer than the chronological time-a well-known psychological phenomenon [15].

The following simple technique can be used to make the motion of a Reflectodyne system respond to sound (Fig. 8). The trees are rotated by a reversible electric motor whose current input is obtained from an electronic circuit consisting of a microphone, amplifier and a two-way relay. Below a given threshold of sound intensity, the relay in its first position sends a current to the motor, causing it to turn, say clockwise, and when the sound intensity exceeds the threshold, the relay flips to its second position and causes the motor to turn in the opposite direction. When rhythmic music or any sound of strong variation in intensity back and forth in phase with the sound input. I have also used such a circuit to control the motion of a kinetic sculpture (Fig. 9).

A circuit with a thyratron in place of the relay can be inserted to cause the intensity of an incandescent lamp to vary in phase with the variation of the volume of sound input.

One of the objectives of the project for the General Electric Co. was to design an audio-kinetic device that would permit ready control of the picture by a viewer. Colors can be varied fairly readily by means of a button control. However, as far as I know, no one has succeeded in finding a way to change conveniently at will the basic character and style of a kinetic picture, that is, say, to change circular shapes into rectangular ones with a different succession of arrangements of them. This can be done with the Reflectodyne system by opening the case and replacing one set of trees by another but few viewers are likely to find this a satisfactory procedure. It may be that a viewer-controllable system cannot be constructed without going to prohibitive complexity and at too high a price for large scale home use.

Neither my audio-kinetic objects nor those that I have seen made by other artists strike me as being aesthetically satisfying. Viewers are at first awed when they realize that the motion or the light intensity of a kinetic picture is controlled by a sound input but this effect soon wears off. Since this article is concerned primarily with the visual aspects of electric light in art rather than with sound, I shall not probe further the problems of audio-kinetic art. I should add that I do not know electronics well enough to construct such circuits and I have turned to electronic engineers to construct the circuits for me.

Fig. 9. ‘Three Figures, I’

No. 983/1966,

Audio-kinetic sculpture, painted cork and wood,

48 x 52 x 72 cm., 1966.

© DR

| |

My work for the General Electric Co. on audio-kinetic devices terminated not because the project was unpromising but because of the chance replacement of the company’s enthusiastic leader of it by an engineer who was interested in designing a low-price record player for children!

I have constructed a variation of the Reflectodyne system in which the image-making reflecting surfaces, consisting of blades of thin polished aluminum that can move like grass reeds, are put into motion by a current of air supplied by a fan installed in the case.

Artists have also produced kinetic pictures on opaque screens or on walls by reflecting light from shaped polished surfaces and by projecting light through large-scale rotating trees [1-4]. The latter installation provides a viewer both with an illuminated kinetic sculpture or construction and a kinetic electric light picture on the opaque surface.

I find that kinetic art systems that depend on the reflection of light from shaped polished surfaces for producing images on a translucent screen are rather limited as regards the range of subject matter and of styles that can be treated artistically. The light image reflected from a crinkled thin polished aluminum surface has an aesthetically satisfying quality but the design of the image is difficult to control. I have seen an interesting image from a piece of aluminum sheet vanish from the screen while I was trying to attach the sheet permanently to the case and have been unable to make it reappear. Reflectodyne-type kinetic pictures are handicapped further by the fact that they have to be viewed in a darkened room, unless lamps of large wattage are installed with their attendant heat problems. Light intensity from lamps is lost both through the reflection process and by transmission through the translucent screen.

3. Transmission of light through light polarizing and birefringent materials.

This method of making kinetic electric light art offers intriguing possibilities but has not been exploited as much as Lumia systems with reflected light [l-4]. It takes advantage of the fact that light can be polarized, that is, when light is transmitted through a polarizing plastic sheet or polarizer, only that fraction of incident light passes through that has its transverse vibrations in a particular plane parallel to the optical axis of the polarizer.

If a piece of polarizing materials (manufactured in sheet form by, for example, the Polaroid Co., Cambridge, MA 02139, U.S.A.) is turned relative and parallel to another piece, then one obtains during one complete turn two cycles of alternating transmission and non transmission of an incident light beam. If a birefringent material with the property of splitting a beam of light into two beams that travel through the material with different velocities (owing to the material’s non isotropic crystalline properties) is placed in polarized light, effects are caused in the light that, when this light is passed through a second polarizer, give rise to changes in the colors perceived.

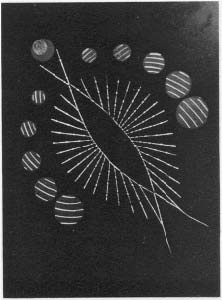

I have applied the 3-component Lumidyne system to make kinetic pictures with polarized light and call it the Polaridyne system. The technique is the following: (1) a polarizer is attached to a transparent or translucent rotor made of polymethylmethacrylate plate (a plastic manufactured under trade names such as Plexiglas, Perspex, etc.) (2) the stator is a sandwich made of a plate of transparent Plexiglas (nearest the rotor) with pieces of birefringent material fixed to it, then a second polarizer sheet and, finally, another plate of transparent Plexiglas.

An example of a Polaridyne system kinetic picture, ‘Three Masks’, is shown in Fig. 10. The birefringent material is ordinary transparent adhesive tape and there are pieces of polarizer included in the sandwich so that in one turn of the rotor there are three different appearances given to the mask when the pieces of polarizer block the passage of light.

I have noticed that viewers of a Polaridyne kinetic picture that has only gradual changes of color frequently do not watch the picture long enough to realize that the colors are undergoing changes. If a shape in motion is introduced into the picture, then their attention is held and they become aware of the color changes.

A chosen color of a patch at the beginning of the cycle of color changes can be obtained by adjusting the angle of the strip of birefringent material relative to the optical axis of the fixed polarizer and by superposing one or more strips at different angles or at the same angle to increase the thickness of a strip. One can make varied compositions on the stator by attaching transparent birefringent material cut into desired shapes and by incorporating designs in transparent and opaque paints or other materials that do not produce birefringent colors.

Fig. 10. ‘Three Masks’

No. 958/1965,

kinetic painting, Polaridyne system,

25x25 cm,

1965.

One of three distinct images produced.

© Barton

| |

V.

The making of an art object involves three major choices: (1) subject matter, content or message of the work; (2) visual conception or code or style to be used for the presentation of the subject matter and (3) technique felt to be appropriate for the execution of the work. I have so far discussed primarily the third aspect because the tendency, beginning with the first pioneers of the use of electric light, has been concentrated on the technical aspects and phenomenal characteristics of the medium. As a matter of fact, both artists and writers on the art of electric light have stressed technique rather than the content and style of the art objects. This is probably due to the fact that the art form is still too unfamiliar and that no tradition of verbal artistic description of works using electric light exists to draw upon. Consequently, artists who have used electric light are noted mainly for their technical inventiveness.

Others who use the basic reflection system of Wilfred or my direct transmission Lumidyne system are said to lack artistic originality and the content and style of their works tend to be ignored. This is an unsatisfactory situation, because there are probably only a small number of possible techniques permitted by the properties of electric light that allow a wide range of content and style to be executed. Artists over the past several centuries have not been judged negatively for using the technique of oil painting but on the results they have obtained with it. One might expect that in time both artists and viewers will become more discriminating in their evaluation of kinetic art works with electric light. Once the novelty of being exposed to the various physical phenomena producible with electric light has worn off, artists will be held accountable for the content and style of their works. Various systems of using electric light will then be evaluated on the range of subject matter and of styles that they allow to be executed.

It is interesting to note that only a few artists have tried to use electric light for figurative subjects. This is in part due to the fact that art with electric light became more common in the 1950’s when nonfigurative or abstract art held the stage in the visual fine arts and when some believed, which I hold to be an error, that an artist could introduce into his works images or ideas that had no relation to the appearance of aspects of external reality. Perhaps the mystical cult of ‘nonobjective’ art is beginning to be replaced by a more realistic attitude. prodded by studies of perception and of the way the human brain works.

Since I have not felt that there was a conflict between figurative and abstract art. I also have made kinetic paintings of the human figure and of landscapes. My exhibition at the Furstenberg Gallery in Paris in December 1965 was criticized by some artists and art writers for containing both figurative and nonfigurative works. The treatment of familiar figurative subject matter by means of kinetic art is undoubtedly tricky from an aesthetic point of view, perhaps mainly because comparisons are made with the vast range of figurative paintings and sculptures produced during the past millennia. Nevertheless, I believe that figurative kinetic art with electric light, of an aesthetically satisfying kind, can be made that adds motion and changes of color to the contemplative experience of fine art.

Whether figurative or nonfigurative subjects are chosen by an artist for his kinetic art works, it should be realized that the aesthetics of motion and of color changes in a work designed for prolonged contemplation are at present poorly understood. Furthermore, the response of the eye to nuances of light images has in the past been but little developed. One can expect that it will be improved now that people are being exposed more and more to light images through the viewing of transparent photographs and color television. These problems need to be given much more attention by psychologists of perception and by aestheticians to help both artists and lovers of art.

VI.

Although the medium of electric light is only slowly being accepted by the art world of industrialized countries as suitable for fine art works, I believe that it will find a place of importance comparable to the traditional media that depend on the reflection of diffuse light from opaque materials. The degree of acceptance will depend on an increase in the number of art schools that offer instruction in the use of the electric light medium and on the number of museums and commercial galleries that expose and offer for sale works in this medium. I am a reluctant prophet, however I would not be surprised if wide acceptance of the medium must await the passage of several more decades.

Whether superior methods for using electric light in art to those that I have described will be found remains to be seen. Every medium has advantages and disadvantages when compared to others. The fact that electric light can be applied readily in kinetic art may give it a great advantage, for, as the public becomes more artistically sophisticated, a much more complex aesthetic visual experience for leisurely contemplation than is possible with traditional static art works may be appreciated and sought.

REFERENCES

1. Image-Kinetic Art: Concrete Poetry, P. Steadman, ed. (London: Kingsland Prospect Press, 1965).

2. F. Popper, Naissance de l'art cinétique (Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1967).

3. D. Davis, Art and the Future (London: Thames & Hudson, 1973).

4. Kinetic Art: Theory and Practice-Selections front the journal LEONARDO, F.. J . Malina. ed. (New York: Dover, 1974).

5. F. J. Malina, “Some Reflections on the Differences between Science and Art”, in DATA: Direction in Art, Theory and Aesthetics. A. Hill, ed. (London: Faber & Faber, 1968).

6. F. J. Malina, Reflections of an Artist-Engineer on the Art-Science Interface, Impact of Science on Society (Unesco) 24, No. 1, p. 19 (1974).

7. R. Vrinat, « Propositions pour une esthétique de la lumière », in F. J. Malina Exhibition Catalogue (Paris: Galerie Colette Allendy, 1955).

8. V. Bonačić, “Kinetic Art: Application of Abstract Algebra to Objects with Computer-controlled Flashing Lights and Sound Combinations”, Leonardo 7, 193 (1974).

9. F. J. Malina, “Improvements in or Relating to Lightpattern Generators”, Brit. Patent Spec. No. 957, 122 (1962).

10. F. J. Malina, “Kinetic Painting: The Lumidyne System”, Leonardo 1, 25 (1968). (Cf. also Ref. 4.)

11 . G. Giusti, “Kinetic Art: Paintings with Electric Light”, Leonardo 6, 145 (1973).

12. A. Michotte, La perception de la causalité, 2nd edition (Louvain: Pub. Universitaires de Louvain, 1954).

13. I obtained a set of the Michotte rotors in 1974 through the kindness of Prof. Jean Ladriere of the University of Louvain.

14. T. Wilfred, “Composing in the Light of Lumia”, J. Aesih. & Art Criticism 7, 70 (1948).

15. E. de Bertola, “On Space and Time in Music and the Visual Arts”, Leonardo 5, 27 (1972).

© Frank Malina & Leonardo/Olats

|