Abstract: The paper discusses briefly kinetic painting systems that have been devised for producing a pictorial composition on a translucent flat surface that changes with time it without resorting to the projection of light through film in a darkened room. The Lumidyne system developed by the author in 1956 is described in detail. Basic principles of its design, together with variations of the system, are given as well as the method of painting used by the author. Examples of several works are shown. The picture produced by the system is considered from the point of view of real motion and of change of transparent colour with time. Then need for aesthetic guide lines jot the kinetic painter is stressed. The author concludes that the Lumidyne system, after ten years of experience with it, is a practical, controllable and economical artistic medium.

1. INTRODUCTION

There are aspects of man's environment and his conceptions of it involving light from the Sun, motion and changes of colors with time that painters have long wished to express in their works of art. But it was not until the last century when the dynamo for the generation of electricity was invented that practical means became available to the painter to enter into this domain of visual experience.

The incandescent bulb and the fluorescent tube are today an inexpensive and reliable source of light, and silent electric motors of small dimension provide a ready source of rotational motion. In addition, the development of modern plastics has made available transparent and translucent plates which are lighter in weight and much less fragile than glass. There is, therefore, no longer any reason why the maker of pictures must limit himself to the use of opaque paints and opaque flat surfaces with which static images have been made since the time of the cave man. And, in fact, in recent years, we have witnessed the development of new dimensions in art involving movement and light, and now commonly called ‘kinetic art’. However, the art world, from millennia long habit, and buttressed by dogmatic and restrictive aesthetic philosophies, has until recently tended to resist this new form of art.

Kinetic art includes visual artifacts of threedimensional or constructional type with mechanical motion of solid bodies, such as animated clockwork systems (which can be found on clock-towers in many cities of Europe) and Calder mobiles driven by air currents. The second major domain of kinetic art comprises the use of cinema equipment to create pictures of changing composition and color projected on to a framed area (the screen). Norman McLaren's work directly on virgin film is a notable example of this technique. Finally, there is the whole range of the less familiar kinetic painting systems, utilizing a translucid screen. In this article I shall discuss in some detail only the last mentioned systems. (I have put the word ‘painting’ in quotation marks, because a more suitable word has not yet entered into our language for dealing with this branch of kinetic art.)

Three principal kinetic painting systems have been devised for producing a pictorial composition on a translucent flat surface that changes with time without resorting to the projection of light through film in a darkened room.

The oldest system, developed since 1905 by the American Thomas Wilfred, makes use of rotating forms made from materials such as mirrors and polished metals [1]. These reflect changing light patterns on to a translucent pictorial surface. Colors of the patterns are determined by transparent colored materials which intercept the light source before the light strikes a reflecting surface.

In the second system, which I developed in 1956, the main composition is painted on a fixed, transparent plate (the Stator), and a design is painted on a rotating transparent disc (the Rotor). Light from incandescent bulbs or fluorescent tubes is transmitted directly through the Rotor and then the Stator on to a translucent plate (the Diffusor) to produce a picture combining light, color and movement. I have called this the Lumidyne system. (It was not until after I had exhibited my first kinetic paintings at the Galerie Colette Allendy in Paris in 1955 that I became aware of the work of Wilfred [2, 3].)

The third system makes use of color changes brought about by the direct transmission of light through polarizing materials, one of the sheets being rotated. The color changes are caused by the introduction of materials between the two sheets that produce birefringent colors.

The Lumia of Wilfred creates a picture the composition and colors of which change with time; my Lumidyne has movement and changing colors within a fixed composition ; and the kinetic paintings utilizing polarizing materials have either a fixed or a changing composition together with changing colors.

The period of time for the repetition of the picture with these systems varies from one or two minutes to a cycle of infinite duration. The cycle for the Lumidyne system with its fixed composition is not readily discerned, even when its period is only one minute, because of the complexity of the movement that the artist can introduce.

Work in the field of kinetic painting consists of two distinct phases. The first comprises the construction of a compact system capable of producing an image with light and movement. There is no reason to believe that the three systems I have mentioned are the only possible ones, as a matter of fact, several variants of these systems arc now being used by artists [4-7].

The second phase consists of creating a satisfying aesthetic visual experience on the translucent surface. It is not difficult to produce interesting visual phenomena but to develop a skill for producing a controlled expression of the artist's intention is another matter.

For several years it was very difficult for me to dissociate my mind from the technical aspects of the Lumidyne while making my kinetic paintings. It was as though a composer for the piano were excessively conscious of the mechanism which causes the strings to make the sounds.

It is interesting to note a tendency in the kinetic art world to give great importance to the technical means for producing kinetic art objects. Until very recently artists in different periods worked for generations with, for example, the mosaic, fresco, water and oil color techniques to express a large variety of visual experiences. It was not expected that each artist would invent a special technique with different materials for his work. One might expect that a limited number of basic, flexible kinetic art techniques will be adopted by artists until radically new technical developments and changing times cause artists to feel that these techniques are inadequate for their purposes.

II. THE LUMIDYNE SYSTEM

1. Basic principles

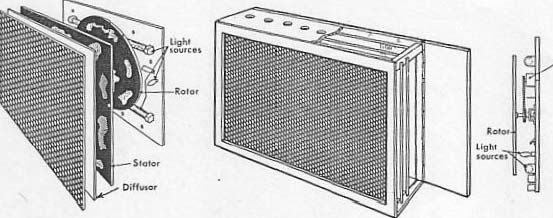

The basic components of the Lumidyne system are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. There is a back board for supporting fluorescent or incandescent lights, an electric motor for driving the Rotor, and reflecting surfaces, such as mirrors. Ventilating holes in the back board and at the top and the bottom of the case are provided to reduce the temperature within the case. The Stator and Diffusor plates arc shown in front of the Rotor. A wire or plastic mesh may be placed in front of the Diffusor to give texture to the picture, and may also be used as a surface for a static painting which is visible when the kinetic painting is not in operation [2, 3].

The Rotor and Stator are made of glass or transparent plastic material; the Diffusor of ground glass or translucid plastic material. Plate thickness of 2 mm is used. Color contrast can be increased by adding a plate of 'black' glass or 'neutral' plastic material in front of the translucid Diffuser plate.

fig.l. Diagram of the Lumidyne system

© Frank Malina

|

A practical advantage of this system is the possibility of keeping the depth of the case to around 13cm. This permits a Lumidyne painting to be hung on walls in the same way as traditional paintings.

The case can be designed to allow easy replacement of the Stator with one of different design in order to produce a different kinetic painting with the same or a different Rotor. The motion of points and areas of light on the Diffusor is determined:

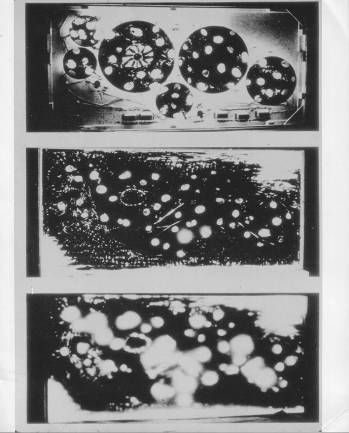

fig.2. Three stages in making a Lumidyne kinetic painting

Photo: Richard Hardwick

© Frank Malina

| |

(a) by the motion of the Rotor, (b) by the arrangement of opaque and transparent areas on the Rotor and Stator and (c) by the distance between the Stator and the Diffusor. For example, consider the case in which the whole of the Stator is painted with opaque paint except for a fine vertical line intersecting the center of the Rotor, and the whole of the Rotor is painted opaque except for a fine curved line bent in a direction opposite to that of rotation from the centre to the edge of the Rotor. Then, when the Rotor makes one turn, on the Diffusor a point of light will be visible which moves vertically upward from the center of the Diffusor until it disappears at the top edge to reappear again at the center and move downward until it disappears at the bottom edge. In this way rotational motion can be converted into translational motion.

If radial opaque bands are painted both on the Rotor and Stator then a rotational movement will result on the Diffusor in a direction opposite to that of the Rotor. This effect is especially pronounced when a line source of light from fluorescent tubes is used.

The distance between the Stator and Diffusor determines the amount of displacement of the light areas on the Diffusor. The more this distance is increased, the less defined will be the radial opaque

lines of the Stator on the Diffusor. I have generally separated the Diffusor from the Stator by a distance of about 2 cm.

It is thus possible for an artist to produce a complex, controlled motion in various directions on the Diffusor pictorial surface even though the Rotor rotates in only one direction.

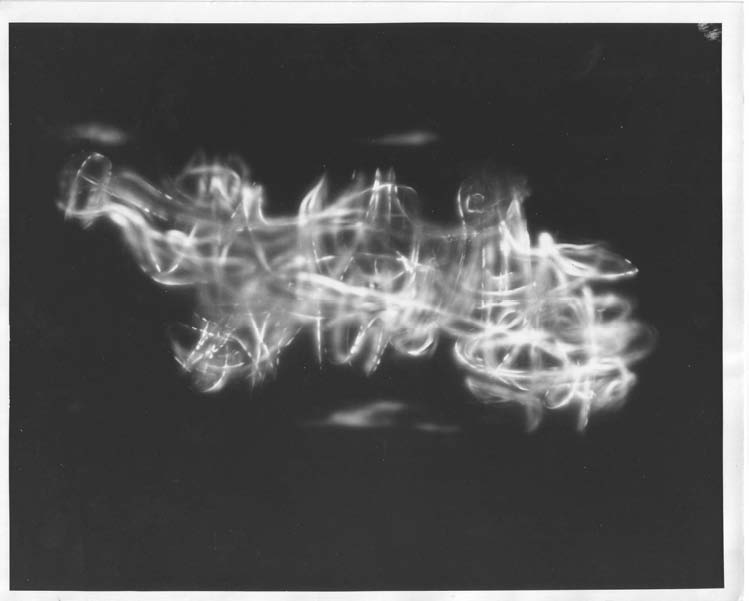

When a structure of fine transparent lines is made on the Rotor and on the Stator, with light originating from clear incandescent bulbs, a pin-hole camera effect is obtained that causes the filaments in the bulbs to appear on the Diffusor in the form of moving bright calligraphic-type characters.

Color changes arc brought about on the Diffuser by painting transparent color areas on either the Rotor alone or on both the Rotor and Stator.

| |

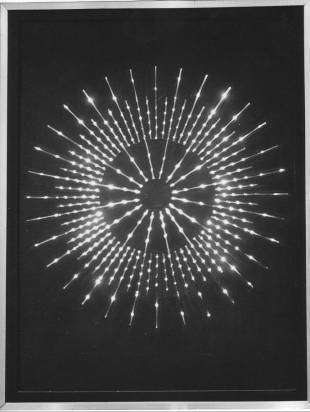

fig.3. "Two Figures VI"

kinetic painting, Lumidyne system (one Rotor)

60 x 80 cm, 1964

Photo: Marc Vaux

© Frank Malina

|

Color combinations result, for example, when a yellow area on the Rotor passes a blue area on the Stator to give a green area on the Diffuser.

By utilizing the principles described above it is possible for an artist to produce on the Diffusor a complex picture of moving light areas and changing colors within the fixed composition painted on the Stator.

2. Method of painting

I have used the following method in painting a Lumidyne. Usually I have a general idea if the composition and the types of motion to he incorporated. A Lumidyne requiring several Rotors and a number of light sources necessarily demands, before its construction, an idea of its ultimate form in order to decide the location of the lights, Rotors and motors on the back board.

It is after the lights and Rotors have been installed that the moment comes to paint designs on the Rotors for producing the desired motion and the basic composition of the Stator. At this stage I use black gouache, mixed with an indelible gouache to facilitate adherence to the plastic surfaces, and I continue to make changes in the design and composition until I am satisfied with the result viewed on the Diffusing Screen. In this sketch stage I use colored cellophane attached with cellophane tape to the Rotor and to the Stator to obtain color effects and changes on the Diffusing Screen within the composition.

The next step is to mark with a grease pencil the designs and colors on the Rotor and the Stator on the unpainted sides of these parts. The cellophane is removed and the gouache paint washed off. The final step consists of painting the opaque portion of the designs with black-board paint and the colored areas in transparent oil paint. Changes can also be made in this final stage until the painting is completed. Examples of completed Lumidynes are shown in Figs. 3 and 4.

fig.4. "Paths in Space""

Kinetic painting, Lumidyne system

100X200 cm, 1962

© Frank Malina

| |

3. Variations of the basic Lumidyne system

For large kinetic paintings a number of Rotors of different diameters and rotated at different speeds may be used as shown in Fig. 2.

Rotors may be mounted so as to overlap, and two Rotors may be mounted on the same axis to rotate in opposite directions. The problems of controlling the motion and the color changes on the Diffusor in these cases become very difficult. I have also given consideration to the possibility of replacing the Rotor by a transparent continuous belt and by a surface given a complex motion by various kinematic mechanisms.

Special effects can be caused on the Diffusor with the basic Lumidyne system by placing opaque or transparent materials between the Stator and the Diffusor. A kinetic circular column utilizing the Lumidyne system is shown in Fig. 5.

Three-component Lumidyne paintings may also be made without the use of a Diffusor by painting a traditional opaque picture on the Stator with transparent lines and areas. In this case the variety of motions that can be introduced is more limited, and the visual quality of the picture is sharper and 'colder (Fig. 6).

III. CONSIDERATION OF THE PICTURE PRODUCED BY THE LUMIDYNE SYSTEM

1. Motion

The age-old craving of artists to express their emotional response to real movement has led to various attempts to give the viewer a sense of motion in static artifacts. An animal has been painted in a pose that could not be maintained in repose : symbols such as arrows have been used to indicate direction of movement ; the Futurists made use of blurring effects and of a multiple reproduction of objects of the kind produced by the stroboscopic effect : the moiré effect has been applied which requires the viewer to move in order to see changes in the picture ; and optical effects have been introduced which give an illusion of motion.

In this paper I shall use the word motion in the generally accepted scientific sense of the continuous change of position of a body or image, relative to a fixed reference point. Motion is characterized by displacement, velocity and acceleration. Furthermore, since the human eye is capable of perceiving only motion of a velocity very much smaller than the velocity of light. Newton's laws of motion are adequate for the discussion of kinetic artifacts, if mass of moving parts is important ; in a Lumidyne. principles of kinematics rather than of dynamics apply.

I shall not attempt to list at length or to classify the kinds of motion that impinge directly upon the human eye or of which human beings have made mental constructs. Perhaps the first motion that intrigued man was the movement of animals, since the earliest known wall paintings were concerned with them. It is also likely that the movement of flames of a wood fire attracted man's attention from the time that man learned to control fire for his own purposes. The fascination of flames persists in our day from the moment a child can begin to distinguish the external world until, when grown old, one sits staring at the flames in an open fire To the play of firelight and the reflections of sunlight has been added in recent times the continuous motion of light and intermittent light signals produced by electrical means.

The motion of water in streams, of wind blown waves on the sea, rain water running down a windowpane, the complex cantilevered flat-spring type of motion of vegetation - leaves, branches, trees, grass - caused by the wind, challenge man to express them in the form of art.

In our world, machines have been constructed which, while serving man, undergo movements of great variety-translational motion of changing speeds as in the automobile, rotational motion of the aircraft propeller, motion in space of a crane hook at a shipdock or at an excavation for a new building. Some motion of machines we not only perceive visually, but we also feel them physically, as for example acceleration in an automobile or an aircraft.

Finally, there are motions which we cannot perceive directly, such as the motion of bodies at a great distance from the earth and at the interior of the atom. The scientist and artist are able to give an appreciation of some of these motions by resorting to abstraction and illusion.

It is well known that some kinds of motion may lead to unpleasant physical and psychological effects. Sea and car sickness are not uncommon experiences. Moving bright lights can be very disturbing. The unbalanced feeling caused by the difficulty of focusing the eyes on an object in which the moiré effect is present has become well known to artists that have used this effect.

Certain movements of light have been observed to cause an effect resembling hypnosis.

| |

fig.5. "Kinetic Column"

Lumidyne system,

158 cm high, 1961 revisited 1967

© Frank Malina

|

In France a device called the Somnidor is manufactured which the maker promises will brine sleep to insomniacs. In this device an illuminated form appears and disappears on a small translucid screen. The subject is told to look at the screen and to breathe at a rate corresponding to the periodic movement of the illuminated form until sleep results.

Although considerable work has been carried out in the field of experimental psychology on visual perception, G. H. Groharn concludes his article on the subject in the Handbook of Experimental Psychology with these words: 'It still has a long way to go. Improved experimentation performed with attention to problems of specification and designed to provide a broad base for theory, will hasten the day when psychology will be provided with an inclusive system of relations to define and explain the phenomena of this important field [8].

fig.6. "Sink and Source"

Three-component Lumidyne system (one Rotor)

60 x 80 cm, 1966

Photo : Barton

© Frank Malina

| |

Recently. J.J. Gibson and R. L. Gregory published books dealing wit h the visual system and the psychol-ogy of seeing that are of the greatest interest to kinetic artists [9, 10].

2. Color

In kinetic painting an artist is primarily concerned with the visual stimulus of transparent color produced by man-made light on a translucid surface. Until this century the use of transparent color was limited in the domain of art to stained glass windows and artifacts made of glass, and the visibility of the colors has been dependent mainly on light originating from the Sun.

For this reason the degree of human appreciation of transparent color has been relatively undeveloped compared to sensibility to opaque color. A person is capable of noting very fine differences in color hue, saturation and brightness in opaque paintings which reflect light to the eye. Color cinema, transparent color photographs and color television are now greatly increasing our familiarity with transparent color.

One should note that in the Lumidyne system, in general, the rules of color mixing are those for colored pigments, since the same light passes successively through the transparent pigments on the Rotor and the Stator. That is the color seen on the Diffusor is a subtractive mixture because each pigment subtracts its quota of energy from the original light [11, 12].

It is my impression that all color combinations adjacent to each other produced by the direct transmission of light onto a translucid surface (the Diffusor) are pleasing to the eye. In other words, certain color combinations do not appear to clash as they do when opaque pigments are used in painting.

3. Change with time in a Lumidyne painting

As I pointed out in the introduction, the Lumidyne system produces a picture with movement and changing colors within a fixed composition (cf. Fig. 3). In the simplest arrangement, where a single Rotor is arid, there is a definite cycle of events which is repeated each [inn the Rotor makes one complete revolution. If the Rotor turns very slowly, say one revolution in five minutes, the motion of light becomes practically imperceptible to the eye, and the observer becomes conscious only of changing colors in rite picture. As the speed of motion is increased by speeding up the Rotor, the various motions of light points and areas dominate the changes in color.

The problems of aesthetics of motion only become relevant when the speed of motion exceeds some lower threshold value. For example, the motion of an hour hand on a clock poses no aesthetic problems of motion. In the same way. one can expect a lower threshold for the rate of change of color with time at which problems of the aesthetics of color change arise. For example, the color changes taking place between sunrise and sunset are not perceived as a dynamic process, but rather as a series of static states. (An exception to this is experienced by the outdoor painter. who experiences frustration because colors change more rapidly than he can make a static representation of the scene he has selected.)

It is interesting to note the period of time persons spend looking continuously at an art object. Studies of this factor have been made by experimental psychologists. From my experience, I find that even for persons who have a highly developed consciousness of visual artifacts a period of one to two minutes is a very long time.

This compares with the capability of persons to watch the cinema, theatre or television for much longer period of time. This is probably due to the fact that such a wide variety of visual and emotional content is presented. and that a story or plot helps to sustain prolonged mental attention. On the other hand, there are few productions that persons wish to see more than once.

It is for these reasons that I doubt that a kinetic art object, which is designed for intimate individual viewing, should follow the pattern of theatrical media. If a story or a well defined plot in time is imposed on a kinetic painting or the painting is not rich in variety of motion and color relationships and changes, then the viewer will soon feel he knows all the answers, and interest in the art object will decline rapidly.

It is possible for the viewer of kinetic art objects to become much better acquainted with motion and color changes than it is for the viewer of cinema or television, for in the lacer it is rare that a re-run of a particularly intriguing portion is made.

4. Aesthetic considerations

As I pointed out in the introduction, the visual artist has long been concerned with real motion and real light, however only in recent times have technical developments provided the means that permit an artist to work directly with these aspects of the visual world without resorting to illusions of them.

There have been objections raised to the use of motion in works of art for intimate viewing because it is felt that static painting and sculpture already give an illusion of motion. Furthermore, the arrangement of forms by the artist imposes movement of the eves of the observer. But what is overlooked, in my opinion, is the fact that a kinetic painting, in addition to stimulating the visual reactions of a static painting, provides visual experiences of real motion and of color changes.

Aesthetic guide lines for the kinetic painter have not as yet been formulated. The artist therefore searches empirically for satisfying visual experiences. It is helpful to take into account the long experience of man with the dance and the theatre and with his recent experience with cinema and television. However, the adventurous and curious kinetic painter finds many surprises and challenges in this little explored domain.

Articles on kinetic art using a vocabulary developed for traditional painting do not appear, to me, to be adequate [4-7 and 13-15]. The problem of verbal description is further complicated by the fact that reproductions in two-dimensional form by photographs or drawings cannot transmit the experience produced by kinetic artifacts.

IV. CONCLUSIONS AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Lumidyne system which I have described, has proved, after ten years of experience with it, a practical controllable and economical artistic medium.

It is suitable for expressing a wide variety of subject matter involving motion and color changes. The more than 100 kinetic paintings that I have made with this system range in size from 25 cm x 25 cm to 3 x 3,5 m.

The system allows an artist to impose his own style on the visual experience finally produced.

Aesthetic principles are still only vaguely understood and provide a challenge for their analysis and formulation.

I wish to express my appreciation to John Villemer for his technical assistance during the development of the Lumidyne system in 1956. Nino Calos aided me greatly between 1957 and 1966 in the mechanical construction of my Lumidynes. Since 1957 he has himself created and exhibited a large number of kinetic paintings utilizing the system. Reginald Weston, Vic Gray. Reginal Gadney and Didier Bouchet have also worked in my studio with the system.

REFERENCES

1. T. Wilfred, “Composing in the Light of Lumia”, J. Aest. Art Criticism 7, 70 (1948).

2. F. J. Malina, Improvements in or relating to Light-Pattern Generators, Brit. Patent Spec. No. 957, 122 (1962).

3. F. J. Malina. Kinetic Painting. New Scientist 25. 512 (1965).

4. N. Calos, « Le Mouvement Réel dans l'Art Plastique », Civilita Macch. 14, 35 (1966).

5. R.Gadney, Aspects of Kinetic Art and Motion (London: Motion Books, 1966) p.26.

6. F. Popper. « L'art de la Lumière Artificielle », L'Oeil. No. 144, 33 (1966).

7. G. Kepes, Ed., The Nature and Art of Motion (New York : George Braziller. (1965).

8. C. H. Graham. Visual Perception, in: Handbook of Experimental Psychology,

S. S. Stevens, Ed., 2nd Ed.. (New York: John Wiley, 1958) Chap. 23.

9. J. J. Gibson, The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin,

1966).

10. R. L. Gregory, Eye and Brain (Kew York: McGraw-Hill, 1966).

11. R. M. Evans, An Introduction to Color (London: Champed & Hall, 1945).

12. D. B. Judd, “Basic Correlates of the Visual Stimulus”, in: Handbook of Experimental Psychology, S. S. Stevens, Ed., 2nd Edn.. (New York: John Wiles, 1958) Chap. 22.

13. R. Vrinat, « Proposition pour une Esthétique de la Lumière », F. J. Malina Exhibition

Catalogue, Galerie Collette Allendy. Paris. 5 July 1955.

14. M. L. Conil, « Tableaux Brevetés », Information et Documents, Centre Culturel Américaine,

Paris, No. 67, 30 (1957).

15. R. Déroudille, « A Propos de ‘Changing Times’ par Frank Malina », Bull. Musées Lyonnais, France. No. 3,45(1958).

16. J. Cassou. « Vers un Art Cinétique », Preuves, Paris, No. 113, 67 (1960).

17. S Koffler, “Malina, Artist-Scientist of the Space Age”. UNESCO Courier. No. 9, 18 (1963).

18 J. Ebara, After ‘Object 2’-Frank Malina, Miss, Tokyo. No. 733, 19 (1966).