Whether or not the special physical conditions and experiences encountered during manned flight in space and during man's sojourn on the Moon and other celestial bodies will significantly affect the visual fine arts is an intriguing question. In this note, I use the term visual fine art to mean: 'the discipline that has the purpose, by means of artifacts, of stimulating human emotions and of deepening emotional perception of selected portions of man's environment' [1].

There are three aspects of 'space-age' art: (1) art made on the Earth with new techniques or materials developed by astronautical technology, incorporating visual experiences provided by space flight and exploration; (2) art made on the Earth to express either the resulting new psychological experiences or the possible new philosophical conceptions of man and of the universe;and (3) art made and used on the Moon and on other planets.

The age-old dream of man to fly in the atmosphere like birds and to emulate the angels and demons of his imagination has been a reality for some 60 years. It is true that only a very small percentage of the Earth's population has flown in aircraft and I know of no professional artist who owns and operates his own aircraft. A case can perhaps be made that aviation has affected the visual conceptions of artists. Some have attempted to give an illusion of the motion of bodies at high speed using traditional painting techniques, in particular, the group in Italy that called itself the Futurists [2]. More recently, some have developed kinetic art to give the viewer an experience of real motion or of change of color with time. Others introduced aviation subjects into their art and used in their compositions, usually called 'abstract', landscape as seen from an aircraft in flight. But, all in all, I do not find an art of the 'air-age' of broad significance from the point of view of visual conception to compare with cubism, abstract art, constructivism and surrealism.

Man's thoughts of voyaging to the Moon and other celestial bodies are of recent origin compared to his old wish to fly. If the longer mental preparation for aeronautics and 60 years of reality have had only a small effect on fine art, can one expect a significant effect to be produced on artists by astronautics ?

A first flight in an aircraft is for most people a greater psychological experience than a first ride either on a horse or in an automobile. A first flight in extraterrestrial space is a considerably amplified experience, as we have learned from the reports of astronauts and cosmonauts.

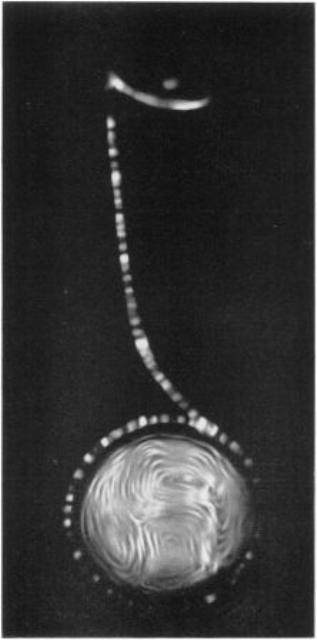

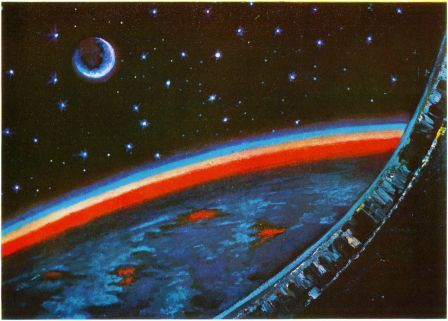

Most art of the 'space age' up to the present time has been in the nature of illustrations of landscapes on celestial bodies that were based either on available astronomical information or on science-fiction imagination and of subjects taken from space technology [3, 4]. These illustrations have generally used the visual conception of producing an illusion of three dimensions on a two-dimensional surface by means of perspective geometry and of chiaroscuro. The Soviet cosmonaut, A. Leonov, has made a number of representational paintings of his experience of seeing the Earth from space (cf. Fig. 1). I have introduced into my kinetic paintings, for example, space flight trajectories and orbits that are a reality but cannot be seen by man or by instruments (cf. Fig. 2). Proposals for future space activities are now being studied in the United States. These proposals include the operation of a research center on the Moon by 1985 with a staff of 50 persons. Staff members would live on the Moon for periods of up to one year [5, 6]. One can expect that art objects will make up a part of the visual environment of the passenger spacecraft for transport between the Earth and the Moon, and of the microcosm created for man on the Moon. The voyage to the Moon only lasts about 60 hours. (To Mars it lasts about 36 weeks-a long enough time to become well acquainted with a work of art.)

If the comparison of man's entry into the domain of extraterrestrial space with man's descent from trees to walk on land has validity, the psychological and philosophical implications for the future of homo sapiens are tremendous. It is worth noting that for the first time in history man will be able to record his actions and reactions when exposed to a major change in his environment.

Fig. 2. Away from the Earth, II

by F. J. Malina,

No .991/1966, kinetic painting, Lumidyne System

200 x 100 cm

1966.

Photo: Unesco Courier, D. Roger, Paris.

© Frank Malina

| |

II.

The two principal new environmental factors that man will encounter during space flight and on the Moon are the absence of an atmosphere (a vacuum of high degree) and zero or low attraction of gravity.

The absence of an atmosphere of sunlight, so that the sky appears black and celestial bodies, such as stars and planets, can always be seen. Shadows are completely black. On the Moon, the lunar day and the lunar night each last about two Earth-weeks. In sunlight, the temperature is higher and in shadows lower than the human body can sustain, requiring temperature control in space suits and in habitations. It is more difficult to judge distances on the surface of the Moon than on the Earth. It is extremely dangerous to look into the Sun and at polished surfaces that reflect sunlight. Also, invisible cosmic radiations (e.g. cosmic rays) are much more intense, since there is no atmosphere to absorb them.

Another important factor to remember is that on the Moon there is no wind as experienced on the Earth. There is a solar wind but man will not be able to sense it. Since breathing oxygen is not available from an atmosphere, he must carry it with him wherever he goes.

Changes in the attraction of gravity also cause important effects. When a body is not accelerating in speed, there results a condition of zero gravity. One has no feeling of up and down; objects become weightless and float in space (cf. Fig. 3). Water will not pour from a glass; liquid drops are spheres. It is not yet known if long-term exposure to weightlessness is harmful to living matter. Eye vision does not appear to be affected.

On the Moon, the attraction of gravity is one sixth of that on the Earth-one doesknow which way is up. Loping seems to be the preferred mode of human locomotion rather than walking. A high jumper should be able to jump six times as high as on the Earth.

III.

As I have pointed out, aeronautics has not, in my view, as yet had a profound effect on the visual fine arts. Artists have much more strongly reacted, through abstractart, to the impact of the camera, to the graphical aspects of mathematics, to studies by physicists of the structure of inanimate matter and by biologists of the secrets of living matter. If astronautics is as significant for the development of man, mentally and perhaps biologically, as some thinkers believe, then one might predict that the artist has much to do now and in the future.

I shall not attempt to present a morphological chart of the large- number of possibilities and permutations that the experiences and the technical aspects of 'man in space' offer to the artist.

From the point of view of technique, in conditions of zero gravity, painting with a brush will be possible but not pouring of paint; sculpture, whether modeled or constructed, will be difficult; lightweight plastics may be suitable. The peculiar behaviour of liquids might be exploited.

On the Moon, an artist will be able to make sculptures of very large size and the cohesiveness of Moon dust may permit the forming of sculptures of very long life, since there are no problems with either wind or water erosion. Wind-driven kinetic objects will not be possible, except in areas of habitation, however, the intense energy of sunlight under vacuum conditions will drive kinetic sculptures by the pressure of light on surfaces. Paints used on Earth may not withstand space conditions for long enough periods of time; painterly techniques used on Earth should be applicable, although, 'action' painting may be affected.

Fig. 1. 'Dawn in Space'

by Soviet cosmonaut A. Leonov.

Reproduced from A. Leonov and A. Sokolov, The Stars are Awaiting Us, U.S.S.R., 1967.

Leonov described the painting with the following text: 'The spaceship is flying over our planet. Days and nights change quickly for the cosmonauts. Their day and night last 90 minutes , i.e. the time that it takes their satellite ship to make one loop of the Earth. So in a period of 24 hours they meet 17 dawns. 'The ship is now flying over the Earth's nocturnal side. The reddish glow of big cities can be clearly seen through the shroud of dark clouds. An irridiscent band of the Earth's atmosphere has appeared at the skyline behind which is the yet invisible Sun. And, above all this, the Moon and bright stars are set against the black velvet of outer space.

|

Fig. 3. Photograph of American astronaut, Edward H. White, ZZ, floating in space secured to the Gemini 4 spacecraft by a 25-ft umbilical line and a 23-ft tether line.

Photo: No. 65-H-1019, NASA, Washington, D.C.

|

It seems to me that the results already obtained at this stage of man's entry into space deserve more consideration by artists working in the field of the visual fine arts. It is certain that, philosophically speaking, we must realize that we have begun, as the Soviet cosmonautical pioneer, Tsiolkowsky, put it at the opening of this century, 'to leave our cradle, Earth'.

REFERENCES

1. Terminology, Leonardo 1, 66 (1968).

2. E. Valli and A. Foschini, I1 Volo in Ztalia (Rome: Editoriale Aeronautica, 1939).

3. Personal profile: Chesley Bonestell, Space Artist, Spaceflight 11, 82 (1969).

4. D. A. Hardy, The Role of the Artist in Astronautics, Spaceflight 12, 14 (1970).

5. The Post-Apollo Space Program: Directions for the Future, Space Task Group Report to the President of the United States (Sept., 1969).

6. F. J. Malina, The Lunar Laboratory, Science Journal, 5,108 (1969).

* American artist and astronautical engineer living at 17 rue Emile Dunois, 92-Boulogne sur Seine, France. (Received 4 December 1969.)