High Tech at the Museum: Tradition and Innovation in the Works of Bill Viola

Jorge LATORRE

1. Introduction

Nothing since the invention of photography has had a greater impact on artistic practice than the emergence of digital technology. While photography revolutionized the arts by superseding painting’s claim to represent the “real”, digital technology has become the ultimate tool for capturing the nuances of the “unreal” 1.

Bill Viola (New York, 1951) is one of the most influential video-creators at the moment, and perhaps one of the most acclaimed international artists. Viola’s image of the world is based on the notion of an integral unit in harmony where the man-nature association is established in a dynamic equilibrium of active and receptive forces. Viola drew philosophical inspiration from many sources. Besides ancient Greece, he was influenced by Chinese Taoism, Tibetan Buddhism, Judean-Christian mysticism and especially Japanese Zen, in which every object or form of life within Nature is acknowledged and considered to possess a spiritual and physical presence. Thus, each object has the same importance in the cosmic system. The organic superstructure (or macro-cosmos) is materialized in each one of the individual structural components (micro-cosmos) 2.

These ideas are quite universal, indeed; and they can explain part of the widespread recognition of Viola’s works thorough the world. However, the most important factor of his success is –and this is the main point I would like to postulate onward- the way how those philosophical or theosophical principles are narrowly connected with technologies being used in a museum context.

At the beginning, for most of the artists that work in a “museum context”, digital technologies are currently associated to the today’s sense that the boundaries between the organic and inorganic, the known and the unknown, the real and the unreal, are being blurred beyond recognition. This feeling was not exclusive to video-creators. In response to the power of simulacrum, a great part of recent practitioners of the plastic arts have turned to more conceptual and anti-technological modes, seeking out the most tangible reality (Land art, Arte Povera, Body art, etc.) in an attempt to provide the material an “almost sacramental” spiritual significance, either inside or outside the museums (Spaemann 2006, 39-55).

This project of recovering the “aura” in the social space with new heterotopias does not draw directly on the traditions of iconology in the history of art. On the contrary, it concludes in someway the iconoclast process which characterizes the historical avant-gardes, since photography and cinema took the role of representation of reality itself, as Regis Debray studied some time ago in Life and Death of Image in Western culture (cf. Debray, 1992). Not only Debray; Adorno and other thinkers from Frankfurt School suggested that, the decline and fall of Western tradition, if it should occur, may be attributed to the influence of contemporary visual culture, which is based on spectacle and the use of technology.

As well, art theorists influenced by the French poststructuralist discourse put in question the very concept of artistic authorship. The development of photography and new technologies of reproduction took a big role in giving root to and spreading this idea. Through reproductive techniques, artists demonstrate the ambivalence of the mimetic notions of individual creativity: there is no possibility of clearly differentiating between the productive and the reproductive, between the original and the repetitive. Douglas Crimp, in his well-known essay “On the Museum’s Ruins”, writes that the new techniques dissolve the museum’s conceptual frameworks, constructed as they are on the fiction of subjective, individual creativity. The re-productive practice causes disarray, and ultimately leads to the museum’s ruins (Crimp, 1997, 202 and ff) 3.

But, as Boris Groys has defended, precisely at the historical moment when the artwork loses its immediately recognizable visual otherness in comparison to a mere thing or to a technically produced media image (Duchamp being the best example), the museum becomes absolutely indispensable to our ability to recognize and appreciate art as art. The less the artwork differs visually from a profane object or a technically produced image, the more necessary the clearly drawn distinction between the art context and the non-museum context of the everyday becomes. Museums are currently more necessary than ever in isolating the contemplative consumer-spectator from the noise of everyday imaginary pollution outside their walls (Groys 1999, 87) 4.

It is also this new productive-consumerist context that makes the museum indispensable for photography, video and computer art that show the normal, the everyday and the trivial events as something new, as different. In the words of Peter Sellars, in the catalogue for the Viola’s exhibition The Passions, “as the 20th century progressed, we discovered that film and video produce recordings of a strangely ambivalent nature, whose characteristics were quickly put to use in a culture of vigilance, pornography and political manipulation. The new materials available to artist and scientist in 20th century carry an extremely high moral price-tag. A number of artists decided to examine the nature of these new materials in greater depth, and to apply the spiritual framework of older technologies in their explorations” (Sellars, 2004, 126-127). 5

2. Et in arcadia ego: time and reproducibility at the service of “aura”

There is no longer need of the museums’ destruction in order to unite art and life, as avant-gardism once proclaimed; nor are they going to disappear in a creative Visual Culture environment, as new modern art museums are built everyday everywhere, especially museums devoted to photography and new media. But it is true that the museum or gallery context changes absolutely when modern technologies go within its walls.

Firstly, it is the art-work itself which illuminates the darkened space, rather than the lighting issuing from outside –focus, natural illumination, etc. This was the traditional practice with painting, sculpture and so on. Given that the material of audiovisual art is light itself, the design and projection of the art-work is planned and carried out in line with its creator’s vision of what constitutes the appropriate intimacy, as well as the environment in which the art-work is to be displayed. Moreover, with the inclusion of audiovisual work in art galleries, light has been wrested from the viewer and delivered into the complete control of the artist.

In audiovisual art-works, unlike fixed-form works of art, the artist also exercises a degree of control over the length of time which the art-work is to be viewed. The time in which they are viewed forms a new part of the visual art form. Thus, although it may be on display in a museum or gallery, the audiovisual art-work parallels the experience of real life, which comprises moments that are of greater or lesser importance. In each instance the viewer may miss what is most significant – kairos, the Greek term for plenitude – because (s)he was not in the right place at the right time. The interactive character of audiovisual experience enhances the rhetorical impact the work has on the audience, but it is its closeness to real life – a strange mixture of freedom and conditioning, novelty and repetition – that gives audiovisual art its extraordinary power.

At the same time, given that the length of time the viewer contemplates the art-work may not match that envisioned by the artist, each cycle of display – each repetition of the projection – may constitute a different experience, even for the same viewer. In his work, Bill Viola succeeds in showing how a more or less autobiographical moment in time may, in a museum space, be removed forever from its original context and rearticulated in a new one. A repeated projection loop manifests the Platonic or Buddhist idea of transmigration or reincarnation: lives within other lives, moments within other moments, times within other times. Life is the re-living, re-creation, re-imagining and remembering of what has been lived for posterity: a family-tree of images. In the words of Peter Sellars, the slow motion camera “is the process of philosophy itself, the close examination of minute detail. In a more radical way than philosophy, perhaps, a recording in slow motion may pave the way to true enlightenment” (Sellars, 2004, 127).

Therefore, Bill Viola has demonstrated that it is possible to use the high tech medium in the “auratic” space of the museums and galleries to evoke the contemplative effects that are still a concern of Art and philosophy versus the Culture of Spectacle. Viola belongs to a generation of American artists for whom the ‘experimental’ is a proud part of the definition of artistic achievement itself; an approach that echoes the spirit of the Renaissance. In a historical period and context (New York and California) for which art and experimental technique go hand in hand, Viola has sought to question and explore the relationship between the nature of empirical reality and its representation, and also between new technologies and museum.

As it was common at the origins of video-creation, Viola began using media in a manner opposite of what occurs outside of museums: that is, inverting his temporal dimension and his visual language, a technique used favourably in “simulacrum”, to pose questions about reality, time, form and expression. These are experiences other contemporary artists represent with different – more traditional - tools. He used the video more as an object than a medium – employing the camera itself as a monitorization instrument.

However, since approximately 1975, Viola started using the camera as a tool of recording and representation which follows the old tradition of producing images, with the novelties of the Media. Viola recalls the art of illusion –from the Latin illudere, to play-, as it was defined by the Greeks, and rediscovered at the Renaissance, from Giotto onward. It could be useful to remember that Vasari, in his famous book The Lives, devotes less attention to the artists’ skills in figurative representation or the imitation of nature than to their use and refinement of the means by which their artistic (and social) function might best be performed: the accurate evocation of a sacred or noble event – that is, the depiction of something beyond the given reality.

The depiction of a transcendent reality is a fundamental attribute of Viola’s works; his digital technology has become the ultimate tool for capturing the nuances of the “unreal”. In other words, it is not “virtual reality”, the effect most commonly associated with digital technology and the arts, which interests to Viola. Rather, it is the expression of the deepest reality, which is mediated from the artist’s universal emotions to those of the spectator. In this case, digital technologies, as in figurative tradition, are only the means but never the end itself.

This notion is well illustrated throughout his work. Take the following examples. In Viola’s The Crossing (1996), the viewer is drawn into a spectacle of light and sound which combines the power of startling effects with the demand that the viewer reflect on what (s)he experiences about deep metaphysical concepts. Viola achieves this dual purpose of though and feeling through the length of time specified to unfold the work and manipulation of the artificial darkness of the museum space. Fire and water, opposing natural forces, consume – and ultimately erase – the artist. Not only does The Crossing show the destructiveness of fire and water, it also discloses their traditional cathartic, cleansing and regenerative meanings.

The Crossing

1996

© Bill Viola

|

Most of Viola’s recent work is marked by the transcendent paradoxes exemplified in The Crossing: the sense of transformation-salvation in death – or in overcoming death. This idea may be expressed in formal or thematic terms as a universal message. However, it is always inspired by the personal need of the artist. Springing from an autobiographical source, this theme can be discerned even in Viola’s earliest work. This is especially evident in Viola’s art since the death of his mother in 1991. The Passing commemorates her leaving this world. It is a complex production with a multiplicity of metaphorical and symbolic allusions to the artist’s prior works, which draw on his experiences over a period of approximately four years, from the birth of his first son to the death of his mother. These two moments provide the framework for the “concentric choreography” of the video (Nash, 1992, 10) 6.

Along with family documents, The Passing also contains a number of images manifest with extraordinary visual power, especially those filmed underwater. The image of a man emerging from water evokes an image of birth, and the longed-for nirvana or paradise. This emergence from another world, one of silence and divine peace, is in fact the image of a man diving into water shown in reverse. This has been read as a rendering of the Christian story of the Ascension, which also appears in subsequent works such as The Arc of Ascent or Four Angels for the End of the Millennium. The roots of this Christian interpretation are disclosed by the artist’s originary mental representation of each human life joining in the eternal circle of life. Actually, using audiovisual techniques to play an image in reverse can be interpreted as an attempt on Viola’s part to show how the facts of human life between birth and death take place within the universal context of cosmic principles, such as an idea of the eternal presence of time.

As with The Passing, the Nantes Triptych, which Peter Sellars has described as “a permanent, defining image of loss”, was inspired by the grief the artist experienced after his mother’s death. In the triptych, some of the documentary images from The Passing and a recording of a birth flank a central ‘panel’ which shows an endless scene of total immersion – a symbol of spiritual life. However, in his most recent museum installations Viola has deferred more to the artificial than to the documentary, and he has been employing techniques common in the Hollywood commercial film industry which often have the effect of inhibiting or preventing contemplation on the viewer’s part. That is, he has move to those audiovisual techniques which frequently are considered part of the world of simulacrum outside the museum walls.

Nantes Triptych

1992

© Bill Viola

|

3. From document to “pictorial” recreation

From The Quintet of the Astonished, which the National Gallery in London commissioned in 2000 as a companion-piece to Christ Mocked (The Crowning with Thorns) by Hieronymus Bosch, to Emergence, which makes explicit reference to the resurrection of Christ, Viola’s work has drawn on Christian themes and ideas. Nevertheless, the meaning of these art-works extends beyond the specific cultural context from which they emerged to encompass all forms of human belief and ways of life open to a transcendent understanding of reality and art. Going Forth By Day, for example, was inspired by an Egyptian papyrus, and was made as a commemorative tribute to the dead – in particular, to the artist’s father, who died in 2000.

The Quintet of the Astonished

2000

© Bill Viola

|

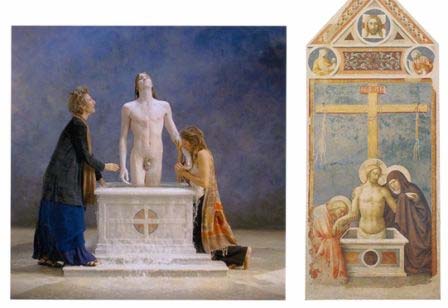

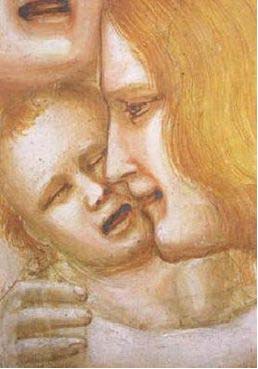

Left :

Emergence, 2002, © Bill Viola

Right :

Pietá, Tomasso di Cristofano (Massolino), 1424. Fresco Museo della Collegiata, Empoli. Photo Scala/Art Resource, New York.

|

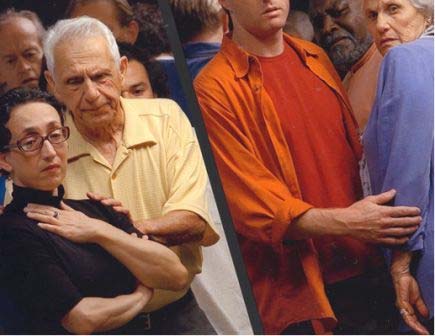

Both Emergence and Observance (2002), which are included in the exhibition The Passions 7, address grief as a ceremony of acceptance and understanding of the death of loved ones, as it happened in the more personal previous works. The perspective in each case is that of the dead, who play the part of the viewer, silently contemplating the reactions of those left behind. Irrespective of the different iconographic traditions by which they may have been inspired (Egyptian, Christian, etc.) or of the narrative point of view they reflect, Viola’s work deals with death as an everyday condition of human life, an idea which finds little place – and even less standing – in the large industry of contemporary arts and entertainment.

Observance

2002

© Bill Viola

|

However, the change in his inspiration and emphasis has provoked a certain amount of criticism. One charge laid against the newer work is that Viola has turned his back on the most challenging formal (documentary) and thematic aspects of his early work. That the documentary value of Viola’s work has diminished may well be true; but there is no sign of a decline in the artist’s preoccupation with contemplation, which is intimately bound up with the silence of the museum.

Another criticism is that his recent works draw on the potential of the most advanced forms of stage (artificial lighting, set design, professional actors on studio, spectacular special effects) and are produced on a budget scale that might be compared to American film production such as The Passion by Mel Gibson which was release at the same time that the exhibition The Passions took place in Madrid (2005). Of course, although both examples draw from the same iconographic roots, there are more differences than confluences between Viola’s and Gibson’s The Passions. Firstly, the way they are going to be experienced –high and low culture- is perhaps the most important. Another difference is the opposing way in which religious subjects that inspire them are “used”: for catechetical purposes in Gibson’s film and for artistic-reflexive-contemplative reasons in Viola’s exhibition (LATORRE, 2005, 103 and ff).

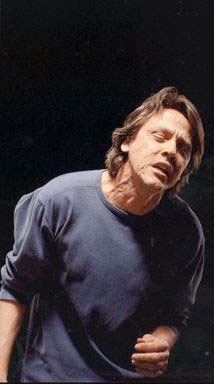

The Passions comprises small-format representations of the face and the hands, along with other more ambitious works in which the artist takes an experimental approach to the movement and relationships between figures in space (Silent Mountain). It is noteworthy that the exhibition does not contain any examples of traditional video art presented as installations or as an ‘environment’. In Viola’s earlier work, the display room itself is the work of art: there is no object; there is only light, sound, and presence. In this exhibition, the art-works are mounted on small stands or hung on the wall, beautiful objects such as framed paintings or carefully worked and detailed surfaces which act – as Rafael Alberti’s famous comment on paintings from the Italian Cuattrocento period note– as windows onto another world. At times, Viola produces a diptych image, a staple mode of religious art, mounting the hinged pieces on a stand (Dolorosa).

Silent Mountain

2001

© Bill Viola

|

Dolorosa

2002

© Bill Viola

|

Most of the images depict solitary figures whose expression of emotions extends over such long a period of time that the viewer is almost obliged to look away and then look back to see if they have changed. The artistic illusion – from the Latin, illudere, play – of which classical and Renaissance artists often spoke is an effect of this surprising sense of change. This illusion is intensified by the movement of bright, high-definition digital images. This reference – and connection – to the history of painting can be made only because of Viola’s use of the most advanced forms of technology. The LCD screen of a laptop computer or a thin plasma screen presents high-resolution images without scanner lines: they provide an infinitely variable frame of representation, yielding images that invite the viewer’s touch and participation, without the disembodied sense of projection used in other, more monumental art-works. Silent images of this kind change as discretely as paintings, with dramatic effects that do not interrupt the contemplative experience on the viewer.

Viola’s incorporation of the contemplative dimension of traditional “musealized” art allows modern technology to reach the simple and profound experience of the first viewer’s gaze; a simplicity which lies at the root of the figurative painting tradition as well as the Golden Age of cinematography. Clearly this approach is not limited to the confines of the Video and conceptual art. It has also been adopted by a number of film-makers throughout the world, from Russian Andrei Tarkovsky to Spanish Víctor Erice or Abbas Kiarostami, whose exhibition entitled “Correspondencias-Correspondences”, has been on display in museums of modern art in Barcelona, Madrid and Paris (cf. Bergala and Balló, 2006).

4. Mimesis at the beginning of Western iconic tradition

Along with their theories, the Renaissance painters’ mastery of perspective and modelling, producing the pinnacle of visual and expressive verisimilitude in painting has been a source of special inspiration for Bill Viola. In the interview for the report on “The Eye of the Heart”, Viola said that in taking his inspiration from Giotto’s frescoes in Assisi he realized that Giotto did not intend for viewers to believe that what they saw before their eyes was real. Rather, he indented that they should look beyond the image to sense the emotion it represented. There is no attempt to hide the fact that the trees, rocks, etc. are made of cardboard because the purpose of the art-work is not to imitate nature, but to achieve the ultimate end of this revolutionary form of art (in the medieval context of the Byzantine iconographic tradition): dramatic narration.

|

|

| Two fragments of Giotto’s frescoes (Assise and Padua) |

If the primary purpose of a painting or a fresco is not to provide its viewers with an illusion of reality but to grant them access to the dramatic moment or emotion depicted on the painted surface, then the use of set-design techniques to reflect the artist’s vision and feeling seems eminently justified according to a long tradition of artistic reflection on the perfect refinement of narrative verisimilitude in images.

Although few complete pictures or images are extant from the Greek classical period, evidence of the classic artist’s ability to create the illusion of reality is found in Pliny’s tales of the competition between Zeuxis and Parraxsios – and, in a more systematic way, in Aristotle’s Poetics and Rhetoric. The last one is perhaps the first systematic study of the emotions in the history of humankind.

Aristotle sought to contribute in a meaningful way to the stable functioning of a democratic society by exploring the public expression of private emotion in ways which were neither exaggerated nor falsified, along with how to observe and control the effects of such expression. This public expression was not a sophisticated form of deceit, but an attempt to communicate valuable ideas for the common good of all. Thus, the theatre was one of the functions of government, and an essential part of political life. In the sacred ceremonial performance of music, poetry and dance at the theatre, all the citizens of the polis could witness the effects of the playing out of the strong and volatile emotions which lie at the heart of tragedy.

Aristotle studies anger and calm, friendship and enmity, fear and trust, justified shame and shamelessness, to analyze the nature of each and the gestures by which they are enacted 8. The Aristotelian idea of mimesis is very different from contemporary notions of the imitation of nature in art; mimesis has a more active sense of re-creation, which gives the art-work its own distinct – if parallel – autonomy with respect to reality, as José Jimenez stayed in his intervention during the International Conference.

In the notebooks he kept while preparing the collection of works comprising the exhibition, now known as “The Passions”, Viola makes a note to himself: “Do not limit your work to the re-production of old, traditional forms; allusions/quotations do not amount to a personal vision”. Although Viola sought out ideas representing a universal anthropology in the themes of either Eastern or Western traditions, he is mainly concern to experiment with new artistic forms and techniques. For example, a source of inspiration such as the face of the suffering Christ in the Veronica’s veil (a negative, printed mirror-image: the Akeropita image -not made by human hands) gives rise to an effective new technique in Memory.

El sagrado rostro (Velo de Santa Verónica)

Francisco de Zurbarán (1598-1664). The National Museum of Fine Arts, Estocolm.

|

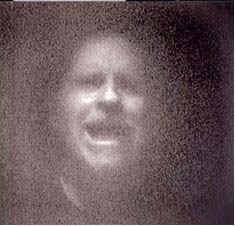

Memoria

2000

© Bill Viola

|

The image of a face emerges in slow motion on a screen as thin as a handkerchief. The grainy texture of the surface appearance produced an effect that suggests the violence and endless creativity inherent in matter constantly subjected to new combinations. The result is a spiritual aura which is, at the same time, immanent by means of its reproduction in a mechanical recording. The image discloses simultaneously a sense of capture and release: the camera has trapped an image, the image a soul; and the soul is trapped between waking and sleep, life and death, this (visible) world and another world which lies beyond the visual (Sellars, 2004, 127).

Art-works such as the one just described help to explain why “The Passions” was the most critically-lauded and visited exhibition of contemporary art in Spain in 2005. The use of audiovisual media as an extension of the function of painting – or, better put, as the recovery of the sense of narrative time reflected in the great frescoes – may provide viewers with an experience of new heterotopias that the frenetic movement of other media such as commercial cinema, television and new digital media does not allow. Viewers respond to this enriching artistic stimulus by filling to overflow the galleries and museums in which Viola’s exhibition are displayed. In particular, works which push back the boundaries of normal audiovisual language querying at the same time the museum visitor on matters of the universal, have made a deep impression on a new generation of artists which find through them a new link with tradition.

In times such as ours, when there is hardly space for contemplation, in which intimacy (a context fundamental for truly moral experience) is dissipated into aggressively materialistic surroundings –a theme vocalised by Bill Viola in The Eye of the Heart (2003)- the most advanced methods of audiovisual expression can achieve results similar to those of the great traditional works of art exhibited in the most important museums around the world. A similar result, indeed, but with much more efficient methods of producing illusion, which do not require interpreter (historian, critic or philosopher) as Danto demanded (Danto 1995, 145). Rather, the artist and the work of art itself suffice, because they are less related to complex meanings than to universal feelings and thoughts that an educated museumgoer can easily understand.

5. Conclusion

Philosophers and writers such as Habermas defended that contemporary art has attained a degree of self-reflection which was earlier the privilege of philosophy alone; and therefore it has made its own definition into its main subject, so that the further, historical, creative development of art becomes impossible (J. Habermas 1990, 43). Nevertheless, Viola’s works show that the use of the most advanced forms of media technology is at cross purposes with neither the tradition of didactic realism in art nor to Avant-gardism’s commitment to the demand for conceptual artistic vision.

First at all, he continues efficiently in the service of art to express the deepest human feelings and questions which in the past full under the purview of philosophy. Secondly, the Viola’s personal use of new language of reproduction is not at cross purposes with the way that the most important painters in the past had once created and thought, from the time of the Greeks to the beginning of twentieth century, when modern visual culture was developing and progressively replacing other traditional ways of depiction. In this sense, his work introduces a deep sense of tradition, which, in a revitalized way, opens the past to the future, and demonstrates that, if the decline and fall of the Western artistic contemplative tradition occurs, it should be attributed to reasons other than the modern media technologies of representation.

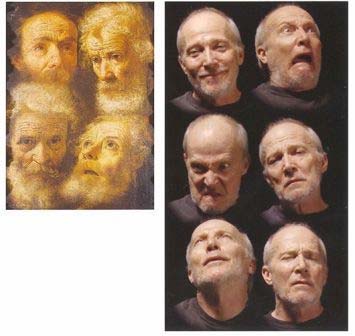

Left :

Estudio de Cabezas, Antonio de Pereda, c. 1650-1675

Right :

Six Heads, 2000, © Bill Viola

|

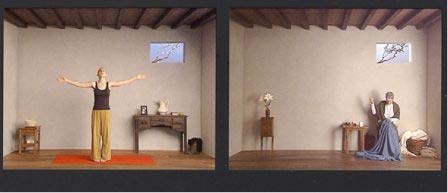

Catherine’s Room

2001

© Bill Viola

|

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ARISTÓTELES (1998) Retórica, Madrid: Alianza.

BERGALA, Alain y BALLÓ, Jordi (edits. 2006) Erice-Kiarostami. Correspondencias. Barcelona: Publicaciones CCCB.

CRIMP, Douglas (1997) On the museum's ruins, Cambridge: The MIT Press.

DANTO, Arthur C. (1995)/, After the End of Art/, Bollingen Series XXXV: 44, Princeton.

DEBRAY, Régis (1992) Vie et morte de l'image, une histoire du regard en Occident, Gallimard.

GROYS, Boris, “The artist as an exemplary art consumer”, XIV International Conference of Aesthetics, Ljubljana (Slovenia), September 1999, volume I.

HABERMAS, J (1990). The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity: Twelve Lectures, trans. F. Lawrence, Cambridge MA: MIT Pres.

HABERMAS, J. The Therory of Communicative Action. Vol. I: Reason and the Rationalization of Society, trans. T McCarthy (1984), Boston: Beacon Press.

LATORRE, Jorge (2005) “The Passions, nuevos lenguajes para temas permanentes”. Nuestro Tiempo, v. 612.

LAWRENCE RINDER, Anne and EHRENKRANZ, Joel (2001), Catalogue of the exhibition BitStreams, New York: Witney Museum of American Art.

NASH, Michel (1992), Introduction to the catalogue The Passing by Bill Viola. Los Ángeles: Museum of Contemporary Art.

PANOFSKY, Erwin, Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art (First edition 1960).

SELLAR, Peter (edit. 2004) “Corpus de luz”, Catalogue Bill Viola. Las Pasiones, Madrid: Caixa.

SPAEMANN, Robert (2001) What does mean that Art imitates Nature?, Art Bulletin, Volume LXXXIII, number 3, September, pp. 559-563. “¿Qué significa que el arte imita a la naturaleza?”, Revisiones, Pamplona: Cátedra Felix Huarte de la Universidad de Navarra, n. 2: 39-55.

VV. AA. Bill Viola. Más allá de la mirada -imágenes no vistas (Catalogue 1993), Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía.

VIOLA, Bill: Statements by the Artist (cat. Exp.), Los Ángeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1985.

VIOLA, Bill (1995) Reason for Knocking at an Empty House: Writings, 1973-1994. Edit by Robert Violette along with Bill Viola, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press; London: Thames and Hudson, Anthony d’Offay Gallery.

VIOLA, Bill (2003) The Eye of the Heart, (PAL video), Poorhouse International, Calliope Media in association with BBC and ARTE, France, 59 mins.

VIOLA, Bill (1988) Bill Viola, Instalations and Videotapes, New York: The Museum of Modern Art.

Notes

1 - Lawrence Rinder, Anne and Joel Ehrenkranz Curator of Contemporary Art, in the catalogue of the exhibition BitStreams, Witney Museum of American Art, New York, march 22-June 10, 2001.

2 - “As man integrates in a complex net of relations with others and with objects, so the cosmic structure must be understood as an organisation of events that exist simultaneously and differ only in their position in space”. LAUTER, Rolf, “The Passing: Recuerdo del presente o dolor y belleza de la existencia”, Bill Viola. Más allá de la mirada (imágenes no vistas), Catalogue exhibition at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, 1993, p. 107.

3 - Crimp has claimed, with reference to Walter Benjamin that through reproductive technology postmodernist art dispenses with the aura. The fiction of the creating subject gives way to the frank confiscation, quotation, excerpt, accumulation and repetition of already existing images. Notions of originality, authenticity and presence, essential to the ordered discourse of the museum, are undermined.

4 - As Groys analyzes, the successful (and deservedly so) mass cultural production of our day is concerned with alien attacks, with myths of apocalypse and redemption, with heroes endowed with superhuman powers, and so forth. All of this is certainly fascinating and instructive, but at the same time it is forever repeating the repertoire of images already collected in the archives, in the museums of our past culture. As a reaction to this, following the self-destructive logic of the system of contemporary art, today’s artist merely consumes trivialities, as every other user or spectator; he is no longer a creator but an exemplary art consumer of art-reflexion versus culture of spectacle and simulacrum.

5 - Though the technological revolution has improved life in many ways, it has also brought deep insecurities over privacy and identity involved implicit exposure of the changing social space. This matter has been one of the most important interests of nowadays Art, specially those artists concerned about modern technology. Cf. Lawrence Rinder, Anne and Joel Ehrenkranz Curator of Contemporary Art, in the catalogue of the exhibition BitStreams, Witney Museum of American Art, New York, march 22-June 10, 2001.

6 - The Passing, in which the artist himself appears, has what appears to be a simple narrative structure: the narration of a dream. The image of the sleeping artist gives way at intervals to a series of more confused images which might be interpreted as memories or dreams. The sleeping artist’s noisy breathing becomes the art-work’s leitmotiv and its sole point of contact with physical reality. At times, the artist’s breathing quickens; and on a number of occasions, in response to the intensity of some of the dream-memory images, the artist wakes for a moment before falling back to sleep. The dream-memory images are comprised of situations and events from the artist’s everyday life (including images of family, especially of his mother), as well as landscapes at night of the Nevada desert, Utah and the area around Los Angeles. At the same time, these sequences are heavily symbolic: a figure walks from the light (a symbol of life) towards a dark tunnel, which is the antechamber of death, the unknown. A woman lights a candle for her son and her grandson – a genealogy of the light of life, which is composed of matter and spirit, wax and flame; and the candle-light eventually fills the entire frame – as eternal Light, a symbol of divine truth, etc.

7 - In 2000, during a year-long residency at the Getty Research Institute, in the company of several critics and art historians, Viola embarked on a series of works exploring the human passions as a universal theme in the history of art. Cf. Catalogue Bill Viola. Las Pasiones, Madrid: Caixa, 2005.

8 - He examines, for example, “the state of mind of one who is calm”, and behaviour among friends: “how to desire for another what would be good for that person, not those things we would regard as good for ourselves”. At the other end of the scale, he explores the definition of fear and its causes as “a type of suffering or agitation which stems from the imagining of some future destruction or painful evil” (quoted in Sellars, 2004, 125).

© Leonardo/Olats, Artmedia X, Jorge LATORRE, 2009

|

|

|